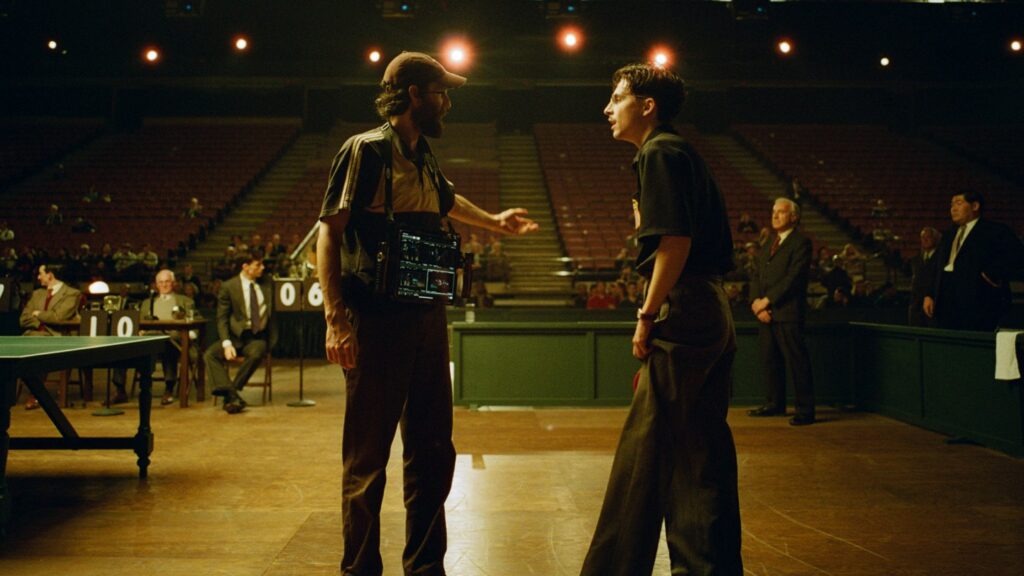

For Josh Safdie, making a movie doesn’t feel worth it without a little theft. In directing his first solo feature since 2008’s The Pleasure of Being Robbed, the New York native — best known for helming stress-inducing films with his brother, Benny, like Good Time and Uncut Gems — quickly realized he’d be working off of a much larger canvas this time around. This meant both more and less room to play.

“In my past films, I had the luxury of being able to just step out and steal shots in the streets,” Safdie says before grinning. “I can’t live with the idea of things not feeling like I’m stealing them.”

It’s a big credit to Safdie that Marty Supreme, which at about $70 million is far more expensive than his previous features, still unfolds with such dangerous spontaneity. This is because of the productive restlessness that Safdie fosters in his colleagues, many of whom have been at his side for decades, and, of course, the spirit of his wildly original new character.

Marty Supreme, backed and distributed by A24, came to Safdie as he was finishing work on Uncut Gems, when his wife, Sara Rossein, handed him a book written by table tennis champion Marty Reisman. The memoir got Safdie’s creative juices flowing — not to tell Reisman’s story (though on the book’s cover, he looked a lot like Timothée Chalamet, who’d go on to take the lead role), but to create a grand ’50s New York tale steeped in this curious sports subculture. Safdie played table tennis as a kid, as did his father; he heard stories of the generations before him who played, too. He knew the milieu intimately.

This helped, since a lot about Marty Supreme would be different from what Safdie had done. He’d never directed a period movie, never worked on the kind of budget this project would require. But he still started out the same way: chatting up his longtime co-writer, Ronald Bronstein.

“When I was a kid, I formed my entire identity in opposition to nursing an aptitude for sports, which probably made me very obnoxious,” says Bronstein of how he first reacted to Safdie’s pitch. “But I do rely on Josh’s natural élan and enthusiasm for life, and the way he takes life in big giant gulps of air. … My brain is a petrified rock. I don’t even have ideas until I’m forced to argue.”

Fortunately, Marty Supreme forced just that. “It’s a shared psychiatric experience where a thought can lead to a recollection of something from the past — something neither of us has thought of since the day it happened — and then we’ll give the floor for that person to ruminate on it, which will lead to an idea,” Safdie says. “One person may think that it’s a good idea, and then it’s time for it to be interrogated in such an intense way that sometimes you forget that you’re fighting for it. You’re trying to find the weaknesses, almost like it’s a courtroom.”

Adds Bronstein: “We’re constantly arguing. Our relationship is predicated on interrogation, and it’s a very invasive process. We’re brutal on one another.”

Marty Supreme follows a wildly gifted, unapologetically cocky aspiring table tennis superstar named Marty Mauser (Chalamet), grinding it in Lower Manhattan circa 1952. He has a clear-eyed goal of ditching his job at a family-run shoe store to compete at the world championships in Japan, but after a series of missteps — including quitting his job and a botched sort-of armed robbery — he finds himself strapped for cash. He embarks on a breathless, high-wire odyssey to cobble together the funds, scheming with his pregnant (married) girlfriend, Rachel (Odessa A’zion), while courting the interest of a local business mogul, Milton Rockwell (Kevin O’Leary), and the mogul’s wife, the semi-retired ’30s Hollywood star Kay Stone (Gwyneth Paltrow).

“Marty was put on Earth being the best at this thing, better than anybody else on the planet,” Bronstein says. “It just so happens that this thing that he’s the best at sounds so stupid to everybody around him. I was like, ‘Oh, there’s my access point.’ What a great conduit to explore the costs that are associated with a pursuit.”

Other Safdie returnees found their own early inspiration. “The movie was about all these different modalities or types of birth — there’s a birth of a new sport, and there’s a birth of the identity of a young man,” says composer Daniel Lopatin. “We were telling this story of a young man with endless, boundless energy.”

Chalamet had been attached early on, having met Safdie at a party when he was first breaking out with 2017’s Call Me by Your Name. The story of a New York striver was relatable to the actor whose training similarly began at the local level, at LaGuardia High School. “There’s this New York connection that I couldn’t even put into words and I’d fail trying to, but that’s just true to my spirit,” Chalamet says. “Having gone through a very similar struggle in New York and playing this guy’s struggle in New York, it was deeply resonant for me.”

As his career skyrocketed, Chalamet spent years quietly training — aided by an expert on the sport, Diego Schaaf — by pulling a table-tennis setup along to productions ranging from Dune to Wonka. Meanwhile, Safdie, Rossein (who served as an executive producer and researcher) and his longtime casting director, Jennifer Venditti, worked to fill out the world around him. Known for her street casting — she refers to her approach as making “the cinema of real life” — Venditti had a much taller task this time, with both a larger ensemble and a fresh period setting.

“Josh didn’t want to use wigs and things like that, so we’re like looking at hair — if someone has a shaved head that can’t work — or if someone has overplucked eyebrows or there’s something with their skin,” Venditti says. “If it’s too cosmetic in a way, if there’s something with the teeth — it’s really paying attention to the faces.” On Bronstein’s recommendation — he’d been a passive Shark Tank viewer for years — she brought in O’Leary, finding he could naturally embody the money-minded rage of a guy like Milton Rockwell. She brought Paltrow back to acting to portray a movie star similarly mulling a comeback. And she told Safdie outright that A’zion was the only actress he should consider for Rachel — even if it took him a bit to come around.

“When I met Odessa on Zoom, at first I didn’t quite get it, which is a real testament to real-life interactions,” Safdie says. “When I met her in person, that was unbelievable. I was like, ‘Oh my God, this is the character.’ “

A’zion felt that way too. “She’s just such a fighter and she’s so independent and I connected to that. She’s fucking badass,” she says. “That part of myself in her, I’m too scared to let it come out sometimes. I admire her a lot and kind of wish that my balls were as big as hers.”

Venditti was tasked with casting extras too, unusual for someone in her role — but crucial to Safdie’s thorough worldbuilding process. The director points to a mid-film scene in a bowling alley, where Marty and his friend Wally (Tyler Okonma, aka Tyler, the Creator) hustle a small-town crew, as an example of its importance. “We personally cast every single face that you see in that bowling alley, and I heard and interviewed a lot of them as well. When they got to set, I never told anybody, ‘Don’t talk.’ I told people to bowl,” Safdie says. “It allows Timmy to feel like he’s actually in a bowling alley in 1952. … It starts off with just this obsession to re-create the world.”

“Everyone knew how unique it was to have an opportunity to be working on an original film with a brilliant director at the height of his powers,” Chalamet says. “Josh is singularly focused and one of the most brilliant, detail-oriented people I’ve ever worked with. He’s as passionate as Marty Mauser.”

Safdie and his team put together individualized books for everyone that ran hundreds of pages and were propelled both by the rich character backstories dreamed up by Safdie and Bronstein and by the contributions of various craftspeople starting their own work. “It’s the faces, it’s the players, what they wear; it’s the locations, it’s clothing,” Safdie says. “It’s pictures of roads in New Jersey. You’d see the department heads on set with these, all broken up and dog-eared.”

The process for Safdie needed to start at production design — because he’d never made a film going so far back in time, he sought out an expert in the field. “I was trying to re-create this footnote of history, and there’s only one person living who is capable of doing that — and that’s Jack Fisk,” Safdie says, referring to the iconic production designer behind such modern historical classics as There Will Be Blood and Killers of the Flower Moon. “Something we talked about early on was [having it] so that I could shoot like a documentary, where you can shoot anywhere.”

Safdie and Fisk began exchanging photographs and contemporaneous films of ’50s New York. They’d go to locations around the city to discuss how they could build out the world in as authentic and detailed a way as possible. “Josh would get just as dirty as I would going into locations,” Fisk says. The verisimilitude rippled out to other departments. Costume designer Miyako Bellizzi, a longtime Safdie collaborator, spent years collecting research in tandem. “It’s like 10 films in one because there’s so many areas of research,” Bellizzi says. “Even the table tennis research and developing 16 countries of uniforms — like, I need to know how people dress in Brazil if I’m going to make Brazilian uniforms!”

Fisk’s greatest challenge in meeting Marty Supreme‘s demands arrived in one of the film’s key areas: the Lower East Side, home to several blocks and areas of shooting. The neighborhood has been totally transformed since the 1950s. Fisk developed a modular system of constructing old tenement fronts to place at the face of buildings that’ve been modernized and power-washed over decades. This is to say nothing of other flourishes to keep entire blocks within filming range immersive to 1952.

For the pet shop where Rachel works: “We just rebuilt the window — took the plate glass out and rebuilt it,” Fisk says. For the shoe store where Marty works: “It was next to a brand-new hotel that didn’t look right, and we couldn’t attach anything to the hotel — it cost a fortune to put anything in front of it — so we developed a system to obscure where we built a lot of signs.”

There was also a ton of guerrilla street decoration. “There were tables out on the curb, then period cars and then people in costumes,” Fisk says. “We had about five layers of activity to look through to see the street.”

They ran out of time at the end of the New York shoot, when they had to nail down a key scene set in a phone booth. Scripted to take place in a diner, they had no immediate access to cobble that together. So they pulled it all off on a New York soundstage.

“We rented a phone booth and built a corner of a building, set this all up in a parking lot right outside the soundstage,” Fisk says. “That night, we shot that scene of the phone call, and then the film was over — and it was something that we thought of within the final 24 hours. It was put together with spit and glue.”

That’s the energy of a Safdie movie. The drama moves as kinetically as the production. “You can only fit so much water in it before the thing overflows,” as Lopatin puts it. “You can’t jam any more water in the thing than the size of the cup.”

But, boy, did they try. The cast got in on the adrenaline. “When I first tried on the [pregnancy] belly, I had a little cloth that I put under, but I was like, ‘I want to feel like a pregnant woman — I don’t want to be able to breathe,” A’zion says. She and Bellizzi worked it out so she was wearing corsets and weights, to fully physicalize the constriction of carrying a child.

“I had a few scars from it because there was some friction from the belly flap under the boob,” A’zion explains. “Being in the car and laying like that for hours and hyperventilating — I had cuts all over my under boob … and it was worth it. It was crazy.”

Cinematographer Darius Khondji, another Safdie veteran, knows the pace well. In this movie’s case, he followed the plan to use classic CinemaScope lenses to add to the realism of the period production. “It gives it this pleasure, this feeling of immediacy — it’s like a scientific document,” he says.

The speed was never more crucial than when it came to the actual table tennis matches, which play out as intensely as any iconic sports-film match. “You can feel how your players are emotionally reacting to every point because of the close proximity of the game,” Safdie says. “We were able to go through thousands and thousands of hours of real points that had been played going back to the ’30s — anything that was documented. We were able to cut together basically a template of what every point would look like.”

Chalamet then studied and memorized these beats. “Those sequences were scripted to a T. … It’s like overpreparation to a hyperbolic degree,” the actor says. “It’s a lot like playing a song in a movie. We had something between 50 and 100 actual sequences, there’s a real rhythm to that, a real art, because a lot of that was practical and a lot of it’s CGI where they filled the ball in.” Khondji looked at boxing films and paintings, including the work of George Bellows, to figure out the lighting system for the matches. “The light falls out on the table and then bounces back on the end — the way it splashes, it’s very interesting the way it lights all around,” Khondji says. “They came in and out of the shadow and it was just very beautiful.”

Chalamet himself also proved a big inspiration for the visuals. “We filmed him almost like a creature, like an insect — it was an anthropological study on a man,” Khondji says. “These CinemaScope lenses that we used for this camera, I felt I was looking through binoculars or a magnifier at this creature, studying someone out in the past.” Bellizzi adds, “He is very similar to how I thought of Marty presenting himself in the film — he’s larger than life. And you dress as the person you want to become.”

Postproduction essentially begins while shooting is still taking place, since Safdie and Bronstein are both on set before editing the movie together. “They are an odd couple,” Chalamet cracks of their dynamic.

“I have a headset, and that headset goes straight into Josh’s ear, and I’m only there to help with rewrites and to catch things on the fly,” Bronstein says. “There needs to be law and order on set.” Safdie puts it this way: “We don’t watch any dailies during production. We enter the edit, and now the director and the writers are morons. I hate them. Ronnie hates them too. And I hate the director, obviously.”

There are entire scenes that Safdie shot before dumping, without even attempting to edit, because he didn’t feel moved by them in retrospect. “If I don’t feel something, it goes in the garbage,” Safdie says. He calls it “starting from scratch.” All told, Bronstein admits “it’s the hardest I’ve ever worked on anything, and I think it was the most rewarding.”

Because the many artisans who worked on Marty Supreme were similarly involved long before there was a finished script, the process for most took years. Still, urgency remained the goal. “It’s almost as if you’re scoring a comic book or something — it’s just like boom, boom, boom. Each cue feels like a panel,” says Lopatin of the music. That energy informed the sound of Marty’s journey: “The needle drops already have a kind of propulsion to them that’s often coming from sequenced synthesizers that are sharp and quick and smooth and digital. They cut through the environment beautifully — and they propel Marty through this universe.”

And what a universe it was. Chalamet remembers when the Marty outline first came his way, before he even saw a script. “I knew I was going to like it, and I loved it,” he says. “I was basically doing somersaults around my apartment with joy.” Cut to the years of training, which Chalamet describes as “somewhere between a marathon and a sprint — it’s really a tremendously athletic sport.” And then the performance itself, which is what we’re left with, through to one last, surprisingly warm close-up. That, too, may be credited to how closely Chalamet related to Marty Mauser.

“Knowing the grind as an actor and not being ignorant to it — my dream wasn’t a financial one like Marty Mauser’s, but it was also in pursuit of an ideal,” he says. “It was in pursuit of a realization of a vision of yourself that you want to achieve in life.”

This story appeared in the Jan. 2 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Read the full article here