“Prosperity is back,” beamed Paramount chairman Adolph Zukor in 1922, noting that the previous year nearly dealt a “mortal blow” to motion pictures. The industry had weathered a storm of growing public suspicion over sordid details coming from the entertainment industry in the wake of producer William Desmond Taylor’s murder and the rape/murder trials and acquittal of comedian Fatty Arbuckle. To ensure future confidence in motion pictures, Zukor helped bring in a self-censoring body to keep the concerned government and public happy. Paramount was coming out of a period of growth.

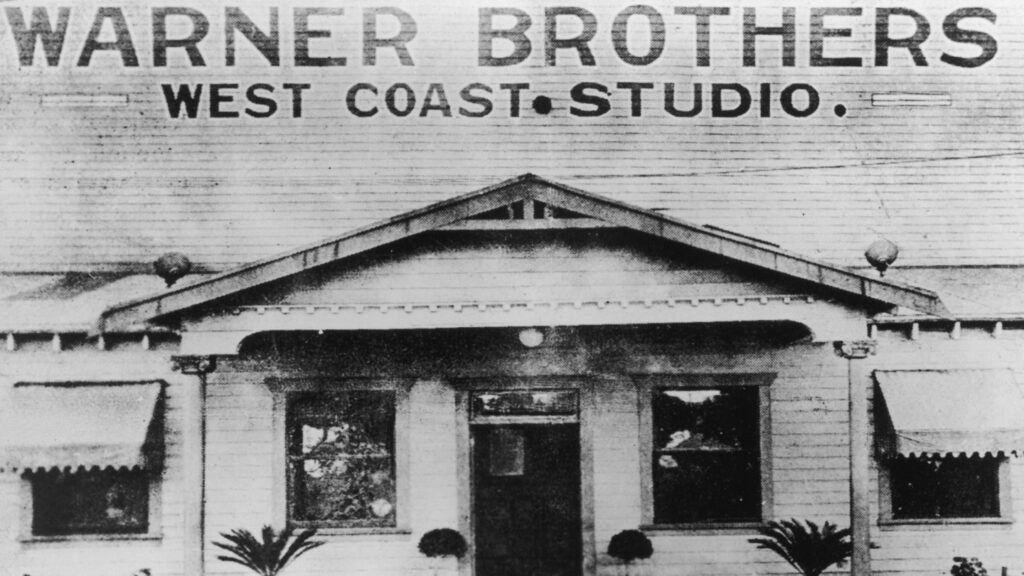

With David Ellison ramping up what may be an ugly battle to force a sale of Warner Bros. to Paramount, the move mirrors Hollywood a century ago when it was also in a period of change amid technological innovation. In the 1920s, Paramount pushed unsolicited offers for the newly incorporated Warner Bros. while Warners pushed back. Zukor streamlined the star system, brought in Postmaster General Will Hays to head up the self-censorship office, and set the bar for rapid expansion in Hollywood. On paper, Paramount had every advantage as Warner Bros. carried debt to purchase studio space on Sunset Boulevard and was arguably vulnerable to a takeover.

The Warner brothers had other ideas. Harry Warner, the eldest brother and studio president, was not to be underestimated or bullied.

Zukor was king of mergers of early Hollywood. His history to that point included combining Famous Players Film Company with Jesse Lasky to create the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation. The Paramount name came from W.W. Hodkinson who created a film distributor called Paramount Pictures Corporation in 1911. Hodkinson was strong-armed into selling stock in 1914 and unseated by Zukor in what was, perhaps, Paramount’s first involvement in a hostile takeover. In the process, Zukor set the movie business on a path towards vertical integration – owning the means of production, distribution and exhibition.

With the freshly acquired Paramount distribution wing, Zukor increased the studio’s output for 1915, all while flying in the face of the newly minted Clayton Act of 1914 that adding attention to maneuvers that restrict competition and harm consumers. Zukor forced Paramount theaters to accept film packages – a mix of desirable and less desirable films – to ensure all product made it through the exhibition network. The practice, called block booking, was the prevailing distribution method until it was rendered illegal in 1948.

About a year after the Warners incorporated their company in 1923, acquisition rumors circled. Harry Warner released a statement to the press assuring their stakeholders and investors that having responsibilities split between the four brothers was “enough of a consolidation” and that Warner Bros. will “remain independent.” Like Zukor, Harry was interested in expansion. Sam Warner was eyeing sound technology and Harry was focused on expanding their theater network. “It is not our intention to own and control a large number of theaters,” Harry told the Exhibitors Herald in 1925. The goal was to place new theaters in key areas controlled by a small number of companies in hopes of adding competition to the market and more choices for filmgoers. “We will fight the monopoly stuff wherever we find it, and we have the money and pictures to do it with,” boasted the Warner president.

The same year found Zukor eager to expand his own theater presence. Zukor’s passion for growth had him referred to as a “bandit” during antitrust discussions in Washington DC. The Paramount executive also became president of the American Motion Picture Association (precursor to the MPA) in 1925, beating out the likes of Marcus Loew, Jesse Lasky, William Fox, Will Hays, Sam Rothafel, Sam Katz, Carl Laemmle, Joseph Schenck, and other Hollywood heavies. By the end of the year, Zukor helped broker a merger between his Famous Players-Lasky theater chain and the houses of Balaban & Katz to become the Publix Theater Corporation. Together, the entity held a little over 500 theaters, but that number would soon grow to well over 1,000 screens.

Meanwhile, thanks to the insight and drive of Sam Warner, his brother Harry invested in sound technology by purchasing Vitagraph Studios, a company with a studio in Brooklyn, cutting edge sound technology used for short films, and a small distribution network. The company was renamed Vitaphone and operated under the Warner Bros. umbrella.

Ensuring the industry knew that Warner Bros. was about to jump out in front of the talkie-producing pack, a star-studded event featuring Vitaphone sound shorts was held at the Warner Theater in New York in August 1926. Among the notables was Zukor, who was increasingly impressed with sound film. MPPDA head Will Hays addressed the crowd, “to the Warner brothers, to whom is due credit for this, the beginning of a new era in music and motion pictures. I offer my felicitation and sincerest appreciation.”

Vitaphone films were used for music and sound effects but would soon be full of dialogue. By May 1927 Warners held one hundred percent of Vitagraph holdings and the year’s end would find the storied premiere of The Jazz Singer, Zukor again in attendance, that solidified the industry’s future in sound production.

The following year, Zukor made moves to purchase Vitaphone from Warners, but the brothers were on the rise and not interested in Zukor’s advances. Warner Bros. was in the process of expanding to Burbank after purchasing the First National lot and distribution wing in late 1928. It appeared as if Zukor’s battles were over. The mogul was very much still waging wars.

“Zukor Yells” read the Exhibitor’s Daily Review, where Billy Wilkerson was a writer and editor prior to founding The Hollywood Reporter. In a precursor to his “Tradeviews” column in THR, Wilkerson’s “Observations” of August 9, 1928 chronicled his call to Zukor to address more rumors of a Paramount-Warner merger. “The sound business is popping. History is being made every minute,” wrote Wilkerson, as Paramount struggled to move up in the early sound market. “The Warners are in the king’s seat and realize it,” wrote Wilkerson, “Paramount wants Vitaphone, Warners know it and Paramount will pay and pay and pay.”

Zukor called Wilkerson to say if he published rumors of Paramount’s struggles to acquire a much-needed rival he would put Billy and his colleagues in jail. A few other publications did run the story and Wilkerson’s pithy response was to surmise that “if Zukor makes good on his threat, as he certainly will, we will, very likely be the only publication on the street tomorrow.”

The whirlwind of trying to corral a merger story isn’t any easier today than it was nearly a century ago. The Department of Justice allowed Warner Bros. to purchase First National in 1928 and the studio’s growth made them increasingly expensive for Paramount. Paramount eventually made enough ground that Variety called a Paramount-Warner deal “imminent” in May 1929. However, reality painted a different picture.

Another trade, The Film Daily, reported the following August that “Washington Authorities have not looked favorably upon the proposed deal” as it was “likely to encroach upon the Federal Anti-Trust Laws.” After all, between the Publix and First National theater chains owned by the two companies, they would have had nearly 2,000 theaters and a guarantee to make money on every film produced. By September, reports of a coming merger remained as Paramount and Warner Bros. upped their stock price by $5 each, $85 and $65 respectively.

Discussions kept grinding away, quietly. Zukor didn’t like the cat and mouse game, but the Warners were growing fast and getting away.

Late 1929 saw a series of renewed internal conferences at Paramount about a plan to acquire Warner Bros. The issue was so pressing Sam Katz, who formed the Publix Theater Corporation with Zukor, apparently cut his honeymoon short to attend one of these meetings. The trades noted Jack Warner and Katz appearing in New York City for merger discussions in September 1929 and remain in the Big Apple for weeks. Billboard announced that deal papers “have been signed” and the studios received a “satisfactory O.K. from Washington on the Deal” after the parties agreed to create a holding company that controls and operates the entities.

Industry insiders revealed that the talks went far enough that they were getting ready to announce what was going to be called the “Paramount-Warner Bros. Corporation.” The masthead would have Adolph Zukor as president and Harry Warner as chairman of the board of directors. Both companies were to remain operating on their own while funneling their films through the Publix theater chain. Variety reported that the merger was “in the bag” in early October but by mid-month the paper was sharing rumors of trouble in paradise on the Paramount-Warner front.

Then the stock market crashed on October 29, 1929.

By November, news leaked that the deal had fallen apart. Beyond the market crash, one issue was that the parties could not agree on how to dilute shares to bring in new investors, with both studios guarding stocks reserved for future expansion. By April 1930, despite national financial chaos, rumors were still flying about a Warner-Paramount merger. Asked about the prospect during a shareholders meeting, Zukor said there was “nothing on the fire right now” but “I cannot say what the future will develop.”

“Govt. After Combines” read THR’s lead headline on January 12, 1931, as Depression Era-America made it difficult for Paramount to acquire a growing studio, not to mention the threat of a revived Department of Justice focus on antitrust activities.

The headlines shifted to a “Paramount-Warner Quarrel” by 1931 as neither company was purchasing films from the other to feed into the competitor’s theater chains. Variety reported that the grudge match was going to cost each company nearly a million dollars a year unless they can find a way to sell to one another again. THR wrote that the “Paramount-Warner feud is being fanned to fever heat” as each company was building theaters in the competitor’s strongholds in Pennsylvania and elsewhere.

The two companies, ultimately, never merged.

When Will Hays addressed the awestruck crowd at the Vitagraph presentation in 1926, he said “no story ever written for the screen is as dramatic as the story of the screen itself.” His words still ring true, as industry heavyweights continue fighting for king of the mountain. The late 1920s and early 1930s were a studio merger arms race not unlike today. We’ve seen the lucrative MGM studio and catalogue purchased by Amazon for $8.5 billion, Disney bought Fox in a $71.3 billion deal, Skydance merged with Paramount for $8 billion, Lionsgate seems perennially on the block, now Paramount wants Warner Bros. Discovery, though the David Zaslav-run conglomerate agreed to sell itself to Netflix for $82.7 billion (a price tag that is likely to go higher no matter who wins WB).

If history is any indicator, it remains possible that, like a century ago, after all the negotiating, fighting, and politicking, nothing will happen between these two powerhouses. Yet, neither Netflix mogul Ted Sarandos nor Ellison show any signs of backing down. One thing’s for certain – merger mania is always contagious in Hollywood.

Read the full article here