Over one billion people in the world are living with mental health conditions, according to the World Health Organisation.

While this means that mental illnesses are no longer uncommon, it does not necessarily mean there is less stigma associated with them.

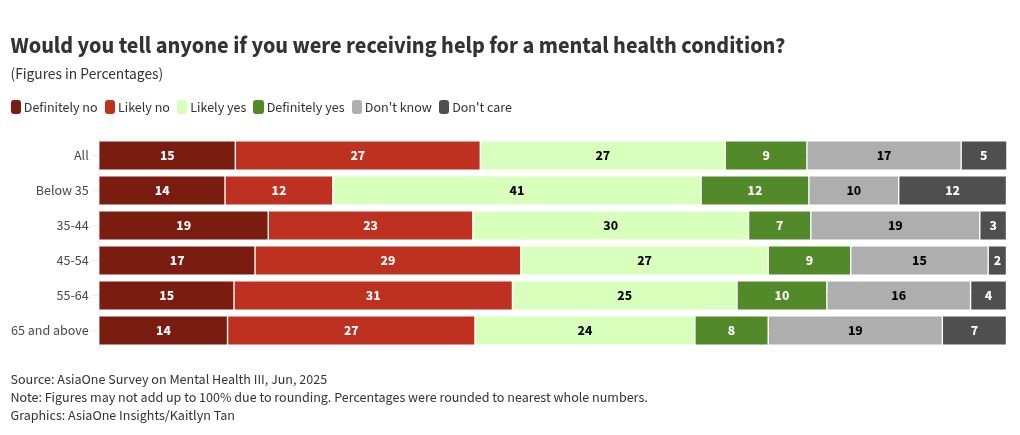

A survey conducted by AsiaOne in 2025, which polled 1,079 respondents in Singapore on their attitudes and perceptions towards mental health, found that 42 per cent of people tend to avoid telling others that they are receiving help for mental health conditions.

Although there is a five percentage point drop from the results of AsiaOne’s survey in 2024, a significant proportion of respondents still gave this response in 2025.

This tendency is especially evident in older respondents (aged 45 to 64), of whom 46 per cent answered that they are unlikely to inform others if they are receiving help for mental health conditions.

This finding raises the question: What deters people from sharing this aspect of their lives with others?

According to James Chong, clinical director at non-profit organisation The Lion Mind, one major reason for this behaviour is a fear of mental health issues being weaponised against them.

“In workplaces, some people worry that disclosing help-seeking may affect promotion opportunities or how their competence is perceived, even when their performance is strong,” he told AsiaOne.

Even in their personal lives, some people are actively discouraged by family members from seeking professional help as mental health conditions are seen as shameful, said James.

“I have also encountered situations where mental health history is used as evidence of instability in legal contexts, such as divorce or custody cases.”

James also stated that there is a strong local culture in Singapore where burnout and physical exhaustion are normalised and worn as a badge of honour, reinforcing the idea that enduring stress is preferable to seeking help.

“Interestingly, many people are supportive of friends going for therapy, yet feel unable to seek help themselves,” he pointed out.

[[nid:714991]]

“There are also misconceptions about therapy, with some believing it is merely casual conversation, leading them to rely instead on friends or religious practices rather than professional support,” he added.

Assistant Professor Paul Victor Patinadan from the psychology programme at Nanyang Technological University’s (NTU) School of Social Sciences echoed similar sentiments to James.

Speaking to AsiaOne, Asst Prof Paul said that longstanding stigma, a low perceived need for treatment, and a high perceived level of self-reliance are key factors which contribute to people not telling others when they are seeking help for mental health conditions.

“We live in a society that values self-reliance and regulation,” he explained, citing research by the Institute of Mental Health that spoke about people perceiving mental health issues as a sign of weakness, not necessarily being ill.

Asst Prof Paul said he also sees what researchers call a “culture of silence” in the workplace, which dictates that the place of work is not “appropriate for expressions of strong emotions and suffering” as well as conversations regarding mental health.

Both James and Asst Prof Paul agree that this manner of thinking is detrimental to society, as it might discourage people from seeking help when they are struggling and perpetuate the misconception that needing therapy or counselling is a sign of weakness.

What needs to change?

If so many people are hesitant to talk about their mental health journeys, what can be done to encourage them to be more open and honest?

According to Asst Prof Paul, the way forward is to co-create safe spaces of non-judgement and compassion by having open, honest conversations about feelings, emotions, and how we handle stressors.

Such conversations allow people to feel that they are heard and are an important first step in moving toward effective help-seeking, he said, adding that one does not need any qualifications to show care and concern for someone in his or her life.

The next step would be to have general knowledge about identifying mental health issues, both in ourselves and others, as well as knowing how to access the channels for care, Asst Prof Paul added.

Although he thinks addressing these issues likely requires a generational shift, James believes that progress is already being made.

Younger generations, particularly Gen Z and Gen Alpha, are already more open to acknowledging mental health needs and seeking professional support, he said.

AsiaOne’s 2025 survey showed that those below 35 years old are more likely to tell others when they are getting help for mental health conditions, with 53 per cent of them saying so.

The results also reflect a shift in views regarding mental health matters, with older age groups becoming more open to discussing them.

In 2025, a lower proportion (46 per cent) of respondents aged 55 to 64 said that they would not tell anyone if they were receiving help for mental health concerns, as compared to the proportion of respondents (50 per cent) who said the same in 2024.

This was also the case for respondents aged 45 to 54 in 2025, of which 46 per cent said they would not tell anyone if they were receiving help for mental health concerns, while 49 per cent said the same in 2024.

James said: “Over time, their attitudes may help normalise help-seeking behaviour, especially if supported by education, open dialogue, and visible role models across society”.

He also believes that meaningful change begins at the systemic level with ministries and government-linked organisations, as well as government leaders and public figures.

Citing the example of Michelle Obama — former First Lady of the United States — who openly shared that she and husband Barack Obama attended couples counselling, he said: “By speaking candidly about this, she helped to frame therapy as a proactive and constructive step rather than a sign of failure.”

Such visibility from respected leaders can significantly reduce stigma and make help-seeking feel more acceptable, he explained.

[[nid:651298]]

Other key findings

AsiaOne’s survey, which was conducted from May to June 2025, also explored how respondents coped with symptoms of mental health conditions.

The most common methods include watching videos, dramas, or movies (39 per cent), sleeping more (33 per cent) and thinking positively (31 per cent).

While the top three coping methods were neutral or positive, some negative coping mechanisms such as binge eating and crying oneself to sleep, were also chosen by a significant number (18 and 16 per cent respectively) of respondents.

Seeking help from a therapist, on the other hand, was selected by just 11 per cent of respondents.

The survey’s findings also revealed that, overall, respondents felt most comfortable discussing their mental health concerns with close friends and mental health professionals.

However, there was a staggering difference in the proportion of female respondents who said they would confide in their close friends (51 per cent) as compared to their male counterparts (35 per cent).

Male respondents, on the other hand, were more likely to confide in their spouses (26 per cent), parents (11 per cent) or anonymously to someone on the internet (13 per cent) compared to female respondents (23 per cent, seven per cent and 12 per cent respectively).

At the same time, both men and women were equally likely (26 per cent) to discuss their mental health concerns with mental health professionals such as therapists, psychologists or psychiatrists.

[[nid:727151]]

bhavya.rawat@asiaone.com

Read the full article here