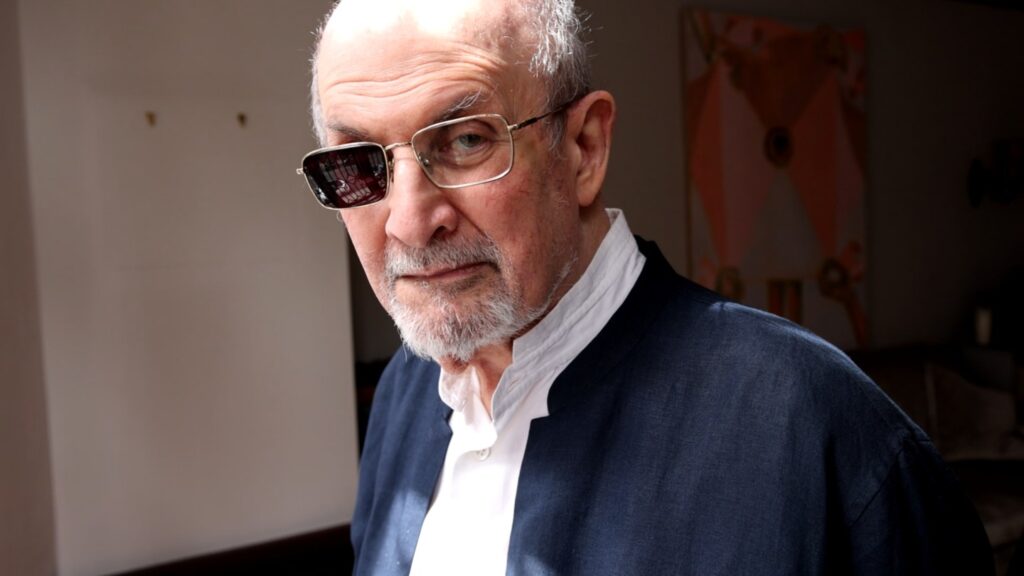

One of the smartest choices of Alex Gibney’s affecting new doc, Knife: The Attempted Murder of Salman Rushdie, is to withhold, almost to the end, footage of the shocking 2022 attack at an education institution in Chautauqua, New York, during which a 24-year-old assailant rushed the stage, stabbing the author of The Satanic Verses 15 times. By that point in this contemplative film, we have seen the vicious assault represented in animated line drawings and witnessed in distressing detail the awful aftermath, during which the gravely wounded Rushdie lay recovering in a Pennsylvania hospital.

But nothing can prepare us for the horrific chaos of the attempted murder, with audience members, security and medics mobbing the stage to halt the attack and urgently tend to the victim. Nor can this clear-headed account of the ordeal and the sheer human resilience required to survive it — physically, psychologically, spiritually — prepare us for the understated win of Rushdie revisiting the scene just over a year later: “I’m standing up in the place where I fell down.”

Knife: The Attempted Murder of Salman Rushdie

The Bottom Line

A stirringly defiant response to hideous violence.

Venue: Sundance Film Festival (Premieres)

Director: Alex Gibney

Based on the book Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder, by Salman Rushdie

1 hour 47 minutes

Throughout the film, voiceover narration from Rushdie’s 2024 memoir, Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder, is put to highly effective and often poetic use. The immediacy of the author’s words is further heightened by extensive footage shot by his wife, Rachel Eliza Griffiths, following a joint decision to document Rushdie’s treatment and recovery.

They begin that process early in his hospitalization, when morphine-induced fantasies fuel the author’s sense of being suspended between acceptance of death and retreat from it. Gibney illustrates that state of waiting, of staving off what at that time appears to be the inevitable, with the famous sequence from Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, in which Max von Sydow’s medieval knight plays chess with Death on a desolate beach.

Rushdie had been the target of assassination attempts from Islamic fundamentalists for more than 30 years at the time of the stabbing. The death threats began soon after the publication in 1988 of his fourth novel, The Satanic Verses, when the Ayatollah Khomeini, supreme leader of Iran, issued a fatwa calling for Rushdie’s death over what some viewed as the book’s irreverent depiction of Muhammad. The film suggests that the most extreme outrage came from people who had never read a word of it.

Using interviews from that period, Gibney recaps the heated protests, book burnings and riots in Muslim communities around the world; the repeat assassination plots foiled by British Intelligence; and the years of hiding, during which Rushdie was constantly relocated by Scotland Yard for his safety, almost like a hostage.

The film also delves into the author’s childhood in India, with an angry drunk father prone to violent fits of rage; and his move to Britain in his teens for a posh boarding school education at Rugby, followed by Cambridge.

Not one for false abnegation of words distorted by smears, Rushdie doubles down on his right to freedom of expression, defending his dissent from religious orthodoxy. In the early years of his fame as a writer, Rushdie had something of a reputation for being prickly and arrogant, but Gibney’s portrait reveals a man mellowed by time and experience. As he puts it, “We would not be who we are today without the calamities of our yesterdays.”

Moments of direct address from Griffiths, the writer’s fifth wife, make the doc quite personal, observing poignant episodes such as her refusal to let him look in a mirror until nine days into his rehabilitation. That intimacy provides an emotional counterpoint to Rushdie’s more philosophical musings about art and religion, free speech and resistance, violent intent and forgiveness.

The graphic shots of Rushdie’s wounds are startling, none more so than his mangled right eye where the knife was plunged in. We hear about the excruciating surgery to sew his eyelid shut and share the sadness when the patient learns the eye cannot be saved. A maxim his parents taught him applies: “What can’t be cured must be endured.”

What made the incident even more alarming when the news broke in 2022 was the fact that Rushdie had become more relaxed about his security after 10 years of police protection. Especially following his move to New York City in 2000, he attended premieres and literary events and began living almost as a public figure again, albeit staying off social media. He even withstood the renewed howls of wrath in 2007, when he was knighted for services to literature. But when his attacker came out of nowhere, 33 years after the fatwa was issued, it seemed to demonstrate that violent fanaticism never dies.

As always with Gibney’s docs, there’s an abundance of archival material, covering records of Rushdie’s life but also doodling animation, images and film clips that provide a visual correlation to the subject’s thoughts.

The uniquely vicious nature of a knife attack — up close and intimate, unlike a bullet fired from a distance — and the symbolic power of the weapon itself are reflected in clips from Knife in the Water, West Side Story, 12 Angry Men and Psycho, as well as references to author Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy, which features a mystical knife that can cut portals between parallel worlds.

While it feels a fraction overlong, Gibney’s film is a vibrant testament to the intellectual life of its subject. Rushdie imagines what he might say to his attacker, Hadi Matar, who was convicted of attempted second-degree murder and sentenced to 25 years in prison. But Knife is careful to avoid giving the assailant too much space in the narrative, as if compartmentalizing his role was somehow a necessary part of the writer’s rehabilitation.

There’s beauty, simplicity and eloquence in the closing images of Rushdie and Griffiths vacationing in Jamaica, accompanied by the contemplative lyrics of Bob Dylan’s “Love Minus Zero.” “I’m 76 and I’m still going,” says the writer with a smile.

Read the full article here