There is a recently burgeoning genre of documentaries — usually either celebrity or true crime in focus — driven not by aesthetic or storytelling imperatives but by (self-)promotional machinery. They’re unscripted movies or series that look at the life of your favorite ’80s movie stars or unsolved murders as fodder for breathless online reports titled “10 Things We Learned From…” or “[Insert Famous Person’s Name Here] Finally Reveals…”

The emphasis is on revelation and not introspection or reflection. In a way, then, a documentary like Angus Wall’s Being Eddie, a generally amiable and adulatory 90 minutes streaming on Netflix, fails; with its softly hagiographic approach, the director never pushes Eddie Murphy to any place that feels untapped or confrontational, and therefore newsworthy.

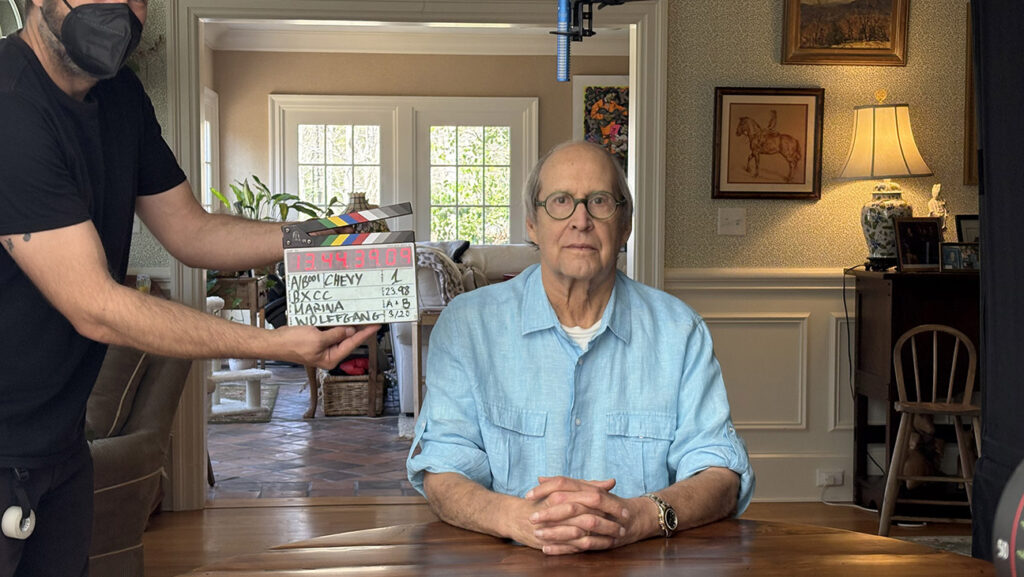

I’m Chevy Chase and You’re Not

The Bottom Line

A complicated, unresolved portrait.

Airdate: 8 p.m. Thursday, January 1 (CNN)

Director: Marina Zenovich

It is by this standard that Marina Zenovich‘s I’m Chevy Chase and You’re Not is most successful. Ahead of its New Year’s Day premiere on CNN, I’m Chevy Chase is already making headlines with its various revelations: his eight days in a coma after heart failure, his disappointment at being unused in the Saturday Night Live 50th anniversary special, his general irascibility even in the face of an authorized documentary.

I’m Chevy Chase and You’re Not is, finally, more about how viewers process these revelations, which almost all serve as various forms of excuse or exoneration for Chase’s well-documented “difficulty.” Do the things we learn about Chase over these 97 minutes make Chase seem like a better person? Possibly a worse person? Or do they just make him seem human in a way that we often deny our stars?

As was also the case with her similarly toned documentaries on Lance Armstrong and Roman Polanski, Zenovich does a better job of acknowledging contradictions in complicated human behavior than reckoning with what those contradictions mean. Her documentaries are particularly flimsy when it comes to linking difficult men with bigger institutional failures. Still, there are worthwhile conversations that I’m Chevy Chase might allow viewers to have.

The documentary presents as a straightforward examination of the rise and self-immolation of Chevy Chase, from quirky college crack-up (he was briefly in a pre-Steely Dan band with Walter Becker and Donald Fagen!) to Saturday Night Live original star (he never had a formal contract!) to movie star to movie star burnout to talk-show host burnout to star and burnout. The basics of the Chase roller-coaster are familiar and well know — that he left SNL too soon, that lots of drugs were involved, that he developed a reputation as a bully, etc.

Zenovich steers immediately into descriptions of Chase as occasionally cruel, often insensitive and, well, an asshole — so much so that she gets deep into the name-calling even before the opening titles. It’s hard to avoid, because I’m Chevy Chase is built around Chase’s on-camera participation, and in that capacity he is undoubtedly an asshole.

“I’m just trying to figure you out,” Zenovich, frequently heard but never seen, explains.

“No shit. It’s not gonna be easy for you,” Chase replies. “You’re not bright enough.”

Unlike this year’s exceptional Pee-wee as Himself, in which the banter between director Matt Wolf and star Paul Reubens quickly emerges as the heart of the documentary, the cat-and-mouse between Zenovich and Chase doesn’t feel productive or based on any artistic tension about presentation and self-representation. It feels like a debate between a documentarian doing her job and a star who probably shouldn’t have bothered to participate at all. He’s sarcastic, occasionally hostile and only willing to engage on his own terms, more likely to respond to a difficult query with performance — at one point he swats an imaginary fly and eats it rather than talking — than explanation or storytelling of his own.

It’s left to a solid assortment of talking heads, with very conspicuous absences, to fill in the myriad gaps. Chase’s brother, half-brother and a couple of college friends illuminate his pre-fame life. Luminaries including Lorne Michaels, Dan Aykroyd, Rosie Shuster and Paul Shaffer talk Saturday Night Live. Goldie Hawn and Beverly D’Angelo do the honors on his movie career; former agent Mike Ovitz chimes in on his professional choices; director Jay Chandrasekhar is left to cover the Community misadventures on his own; and longtime wife Jayni his three daughters offer their insights into the Chevy who has largely lived a quiet life in Bedford, New York, for an unspecified period.

The interviews with Chase provide very few notable details, but he’s far from dead weight. The casual glimpses of his ordinary life in Bedford and public events like his annual Q&As on behalf of Christmas Vacation are sweet and human and capture the 82-year-old comic as a rascal, but not an asshole at all. These scenes make his participation worthwhile; I wish they made up more of the documentary.

In his current form, Chase isn’t a redeemed or rehabilitated figure, but he’s poignant. It’s maybe two-thirds of the way into the documentary, after chronicling lots of questionable Chase exploits, that Zenovich begins with the dark revelations that you’ve probably already read about in news stories.

What’s striking is how little of what’s “new” here relates to previously notorious incidents. Terry Sweeney doesn’t appear on-camera to talk about Chase’s homophobic jokes when he guested on Saturday Night Live in the ’80s; the lack of fresh information is so conspicuous that Zenovich has to read to Chase from Tom Shales and Jim Miller’s indispensable oral history. Yvette Nicole Brown and the rest of the Community cast don’t show up on-camera to talk about Chase’s behavior on the set, leaving nearly everything to Chandrasekhar’s memories.

The fresh headline-grabbing material is presented so that even if it isn’t exonerating, it’s placed to build sympathy: We learn about the abuse he experienced as a child, the depression he felt after the swift cancelation of The Chevy Chase Show, the memory loss he’s experienced after his hospitalization for heart failure.

There’s no direct connection between any of these things and Chase’s negative actions, but they all fit under the documentary’s overall classification of Chase as “not a good man but an understandable man.” The abuse contributed to harsh humor as a defense mechanism; the drugs contributed to harsh humor (punching down as much as up) that he couldn’t or didn’t control; and the memory lapses that he exhibits when Zenovich directly questions him about the Sweeney incident and more — well, it’s plausible that he truly doesn’t remember, which is simultaneously all-too-convenient and uncomfortably inconvenient.

What does the documentary gain from the director asking Chase to account for things he actually might not remember, other than avoiding accusations that Zenovich didn’t ask the tough questions? If Chase truly does have a currently diminished capacity, then the film offers no perspective on things he did that weren’t good; it just makes us feel bad for judging their badness.

Plus, plenty of other people also bear responsibility for Chase’s behavior and aren’t taken to account. Sure, it’s nice that Lorne Michaels showed up to toast his old pal, but he offers no justification for all the times he brought Chevy back to host SNL even after the Sweeney incident. Nor does he do much to counter Chase’s feelings of palpable disappointment at how he was marginalized for SNL50. Chandrasekhar is a poorly chosen avatar to address all the toxic behavior that took place on Community, a bizarre workplace situation that nobody at NBC has ever properly explained.

It’s one thing for Chase’s daughters and beloved co-stars to say that the Chase we don’t know is a caring, sweet man, which I would never dispute. But there’s a serious conversation to be had about what it means for certain types of genius to be professionally enabled at any cost. It’s obviously Chevy Chase’s fault that he developed a reputation as an asshole over 50 years in the business, and a few of the talking heads of lower stature in the documentary are willing to discuss their own negative experiences frankly. But if nobody is going to make Lorne Michaels or anybody else on his level reckon with the nature of an industry willing to do a cost-benefit analysis, if nearly everybody in the doc just chuckles about Chase’s actions like they’re business-as-usual, what does it say about the business?

Those unanswered questions play into the title of the documentary, which references Chase’s famous Weekend Update intro, but in this context suggests a layer of tragedy as well. Young Chevy used the line as an exaggerated, but not wholly feigned, superiority, but is it good or bad to be Chevy Chase? Is it good or bad to have many of your respected co-workers think you’re an asshole, but to have a wife and daughters who know you’re not? Zenovich opens the door for these conversations, even if she doesn’t delve into them directly and even if they’ll never be fodder for clickbait.

Read the full article here