Garth Hudson, the majestic keyboard, saxophone and accordion player and last surviving member of The Band, died Tuesday. He was 87.

Hudson died in his sleep at a nursing home in Woodstock, New York, his estate executor told The Toronto Star.

The Canadian musician and his mates Robbie Robertson, Levon Helm, Rick Danko and Richard Manuel backed up Ronnie Hawkins and Bob Dylan before striking out on their own. They perfected a style that combined American roots music, country, blues, R&B, gospel, rockabilly and — courtesy of Hudson — tenor sax and organ dirges.

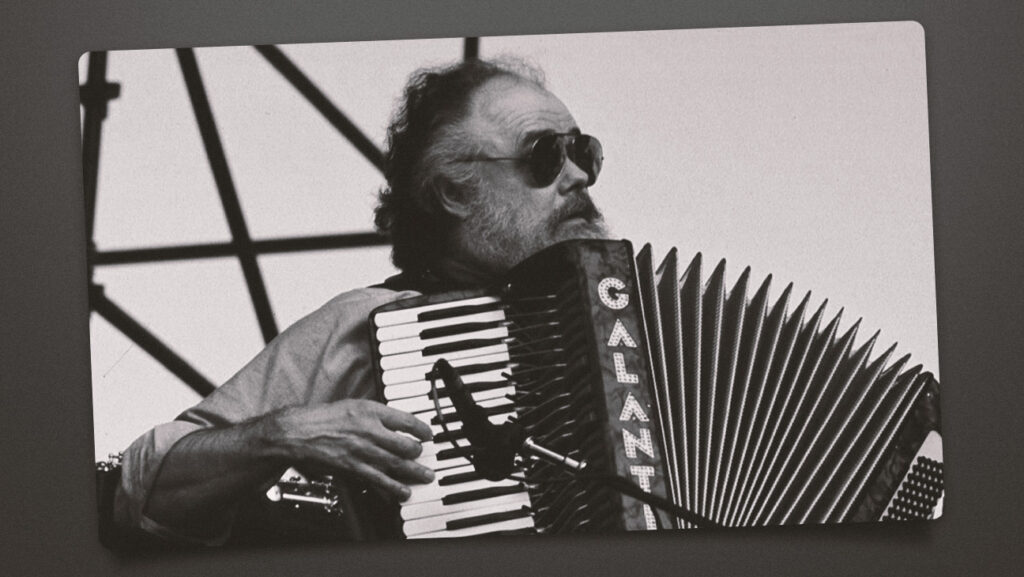

One of many highlights of a Band concert was the bearded Hudson as mad genius performing an organ solo and a standard improvised introduction to “Chest Fever,” from their seminal 1968 debut album Music From Big Pink. The tune, written by Robertson and echoing Bach with its classical overtones, opened their Woodstock set in 1969.

“Where most rock organists 15 years ago were infusing their organ work with the razzle-dazzle of gospel, Hudson cultivated a more pastoral sound,” Keyboard magazine wrote in 1983. “Unlike Billy Preston, Felix Cavaliere, Alan Price and in a different sense, Ray Manzarek and Doug Ingle, Hudson worked in the background, letting the rhythm instruments and vocalists in The Band stand in the footlights while he spun his intricate musical webs so deeply into the fabric of each song that it was almost impossible to separately identify the keyboard parts at all.”

Eric Garth Hudson on born on Aug. 2, 1937, in Windsor, Ontario. His parents, former World War I fighter pilot Fred James Hudson and Olive Louella Pentland, played instruments.

The family moved in 1940 to London, Ontario, and Hudson attended Broughdale Public School, Medway High School and the University of Western Ontario. Along the way, he studied classical piano and played the organ at St. Luke’s Anglican Church and at an uncle’s funeral parlor.

As rock ‘n’ roll was taking off in the late 1950s, Hudson performed with dance bands and began a three-year stint as a member of Paul London & the Capers in 1958.

Robertson had already moved from his home in Toronto to Arkansas to hook up with Hawkins’ backup band, and in his 2016 memoir, Testimony, he recalled pitching the rockabilly barnstormer on having Hudson come aboard.

“You remember Garth Hudson? Well, I talked with him and besides being a really skillful musician, he’s a fascinating and unusual guy,” Robertson wrote. “He mentioned this new gizmo that hooks up to a piano and sounds like an organ. It would make us sound twice as big.”

He also mentioned that Hudson played various saxophones. “Yeah, to have an organ and horns, that would be a big sound,” Hawkins said.

However, it did take some convincing for Hudson, then 24, to leave his parents’ home. The clincher, Robertson recalled, was that Hudson got an additional $10 a week to give music lessons to his bandmates. (That assuaged his folks, who feared their son was squandering his education.)

“Just having Garth as a teacher was an honor,” Helm wrote in his 1993 memoir, This Wheel’s on Fire, saying he learned a great deal about chord structures and harmonies from Hudson.

“He’d listen to a song on the radio in the Cadillac and tell us the chords as it went along,” Helm recounted. “Complicated chord structures? No problem. Garth would figure them out, and we found ourselves able to play anything.”

From 1961-63, the small-town Canadian kids and the Arkansas-born Helm played all over southern Ontario with Hawkins. Hudson brought along his Leslie speaker cabinet and a tricked-out Lowrey organ with wah-wah pedals.

After leaving Hawkins in early 1964, the quintet, now called Levon and the Hawks (and briefly the Canadian Squires), toured on their own across North America. Once, they all got busted for possession of marijuana, but only Danko was charged, receiving a year on probation.

Hudson, Robertson and Helm backed singer John Hammond on a 1965 album, and in September of that year, the Hawks auditioned for Dylan at Friar’s Tavern on Yonge Street in Toronto. They were with him when he shook up the folk world by switching to electric guitar on tours in 1965 and ’66.

During one stop at Toronto’s Massey Hall, Dylan faced derision from folk music lovers in the audience, and one local reviewer criticized Dylan for playing with a “third-rate Yonge Street band.”

“Only Garth seemed to understand why this was happening and chalked it up as a sign of the times,” Robertson wrote in his memoir as the rest of the band took the criticism personally.

“It was a job. Play a stadium, play a theater,” Hudson told Maclean’s magazine in a 2002 profile. “My job was to provide arrangements with pads underneath, pads and fills behind good poets. Same poems every night.”

In 1967, the Hawks accompanied Dylan to his pink ranch house in Woodstock as he recuperated from a motorcycle accident. In the fall and winter of that year, they collaborated on the bootleg recordings that would be known as The Basement Tapes.

“The typewriter would be there and Bob would tap on it for a while and then someone would go downstairs to check the equipment and then finally everyone would go down the pink stairs” to record more Dylan demos, Hudson recalled in a 2014 documentary in which he returned to the “Big Pink” house and toured the cellar.

In 1968, the five musicians became simply known as The Band and released Music From Big Pink, which Rolling Stone in 2003 listed as No. 34 on its list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.

During the next eight years, they would record and release eight albums and hit songs including “The Weight,” “Up on Cripple Creek” and “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.”

The Band called it an era with a legendary final concert on Thanksgiving 1976 as captured in Martin Scorsese’s The Last Waltz (1978), but Hudson launched a solo career and reunited with Helm and Danko for a new album, Jericho, ultimately released in 1993, followed by two more LPs.

He also contributed music to Scorsese’s The Raging Bull (1980) and to Philip Kaufman’s The Right Stuff (1983) and composed a 1980 score for a Los Angeles exhibit by sculptor Tony Duquette called Our Lady Queen of the Angels that became an album.

The Band was inducted into the Canadian Hall of Fame in 1989, and in 1994, with Hudson’s trademark bushy beard nearly all gray, entered the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The humble organist used his address to name just about every musician he ever played with or was influenced by, including the Gipsy Kings, Leonard Cohen, Van Morrison, Muddy Waters, Marianne Faithfull, Roger Waters, Jennifer Warnes, Cyndi Lauper and Clifford Scott.

In 2001, Hudson released his first solo album, The Sea to the North, but he also filed a third time for bankruptcy protection that year.

Lawyer Michael Pinsky told the Daily Freeman newspaper that his client was “bravely working through several challenges, including the death of former partner Rick Danko,” he said. Danko was 55 when he died in December 1999 after years of alcoholism and drug addiction.

He was named a Member of the Order of Canada in 2019 for “his unique musical contributions and for his mentorship of many emerging artists over the past 60 years.”

In 2017, Hudson, then living in obscurity in Woodstock, performed as part of a “Last Waltz 40 Tour” to mark the 40th anniversary of The Band’s farewell concert. He emerged in April 2023 to play “Sophisticated Lady” on the piano from a wheelchair at a house concert in Kingston, New York, hosted by fellow keyboardist Sarah Perrotta.

His wife and frequent bandmate, singer-actress Sister Maud Hudson, died in February 2022.

Read the full article here