For nearly a decade, the unfinished Oceanwide Plaza complex in downtown Los Angeles has stood like a gargantuan, gleaming question mark: a three-tower, $1.2 billion project that stopped halfway to completion. Then it became something far worse.

After construction halted in 2019 when the Beijing-based developer ran out of cash, the skeletal high-rises across from Crypto.com Arena became an open invitation to the streets. Taggers took on the challenge in 2024, covering the trio of skyscrapers from top to bottom in the colorful scrawl that gave it its current nickname: “Graffiti Towers.” They made their global debut at that year’s Grammy Awards.

Two years later, the unsightly landmark has finally cleared a major legal blockade by reaching a bankruptcy exit deal with its creditors, opening the door for a sale.

According to a Jan. 28 court filing, first reported by Bloomberg, lawyers for Oceanwide argue “a prompt sale and eventual completion of the project is a major priority for the city and the public at large, particularly with the upcoming 2028 Olympic Games in Los Angeles.”

Indeed, the Games offer a new sense of urgency and a potential hard timeline for a solution. With the world’s attention heading to this city in just over two years, officials and civic boosters are suddenly wondering if the most glaring scar on the city skyline can actually be cleaned up before the Games.

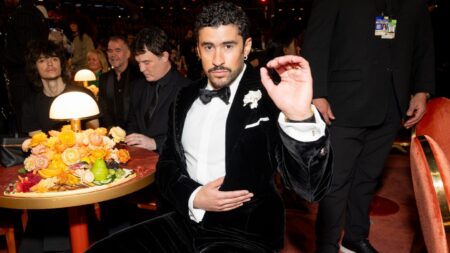

Part of the answer has spilled out into Los Angeles politics. In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, billionaire developer Rick Caruso, whose development work and 2022 mayoral bid made him a familiar voice in local civic debates, publicly criticized city leadership for what he calls a failure to manage the Graffiti Tower situation.

That broadside put pressure on Mayor Karen Bass and the city, which in the days and weeks following the tagging orgy scrambled to respond.

In recent years, the Los Angeles City Council voted to strengthen fencing and increase police presence to deter trespassers, and at times pushed for private security and cleanup funds, though those efforts have often struggled to move from resolution to reality.

The XXXIV Olympiad looms large in these debates because the site’s location — in the shadow of a major competition venue and expected visitor corridors — makes its derelict state especially conspicuous. Leaving a graffiti-covered complex dominating key sightlines through 2028 would be an embarrassment, not just for local residents but for the city’s global brand.

But even with the bankruptcy deal clearing legal hurdles, the practical and financial obstacles to cleanup and completion are considerable. The graffiti itself is the easiest part of the problem to describe; removing it across dozens of floors without modern facades, while securing and repairing the underlying structure that has sat exposed and unfinished for years, is far harder.

Any buyer willing to take on the site still faces millions in construction costs, ongoing maintenance, and the broader challenge of making it viable in a post-pandemic, high-cost market.

City leaders can leverage the Games to speed permitting, push for redevelopment incentives, or even help underwrite cosmetic improvements, yet all those steps depend on finding a developer capable of rehabilitating the project on a tight schedule.

Bass and her administration have responded intermittently over the past two years, largely framing the situation as a public safety and trespassing issue. When videos circulated showing people paragliding off the graffiti-tagged towers, the mayor warned publicly that “tragedy will take place…if that place is not boarded up quickly” and said the city would erect new fencing — though noting it would take time and that the property owner should reimburse the city for costs.

There were also moves through the City Council to step into the cleanup process. In early 2024 the council approved roughly $4 million to beef up barriers, bolster security, and remove graffiti if the developer failed to act. Some council members pushed to have the city take action and recover costs from the owner.

But that city-driven cleanup effort has stalled — in part because of legal and financial hurdles. In early 2025 the city quietly decided not to spend taxpayer money to scrub the graffiti off the privately owned towers, citing a determination that it was not its responsibility to incur the costs of abatement on private property.

Mayor Bass did not respond to a request to comment for this story.

Read the full article here