“They want crap,” Carolco executive Peter Hoffman once told the Los Angeles Times, “Every time people tell you they don’t, it’s bull. They want crap.” Hoffman was reflecting on the lackluster audience response to the Oscar-nominated Music Box (1989), while sci-fi action blockbusters such as Total Recall (1990) were filling coffers like mad.

Long before independent production houses like Skydance, A24, and Blumhouse were making waves alongside the major studios, Carolco made its name in Hollywood as a backer of lavish action films that included the Rambo series, Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) and Cliffhanger (1993). Carolco’s rise and fall was as epic as one of their blockbuster action films.

It was known as “The Carolco Premium.” While rival indies TriStar and Orion had their share of respectable projects, Carolco led a rise of independent studios by creating and maintaining a blockbuster brand for making the most extravagant actions films of the era. The excess wasn’t just on the screen, either. It was lavish salaries, a private jet and a yacht parked at Cannes for the festival’s most desired parties.

The company enjoyed a strong reputation for delivering the defining films of the first major action era until its demise nearly 30 years ago in 1995. As an independent, Carolco focused on films with mass-market appeal to minimize risk alongside extreme budgets. During its time, Carolco courted visionary and risk-taking directors like Walter Hill (Extreme Prejudice), James Cameron (Terminator 2), Paul Verhoeven (Total Recall, Basic Instinct), Oliver Stone (The Doors), Roland Emmerich (Universal Soldier, Stargate) and Adrian Lyne (Jacob’s Ladder).

Wealthy immigrant-American founders, Mario Kassar and Andrew G. Vajna, created Carolco in 1976 to distribute U.S. films abroad. In 1978 Carolco financed 50 percent of The Silent Partner and took advantage of then-new Canadian tax incentives to film north of the border. In 1979, Kassar and Vajna inked a deal to distribute six films in Italy for a deal that was reportedly over a million dollars. With this kind of global buy-in, it was time to make bigger films with bigger stars. By 1980, they began financing their own films.

Corolco’s major reign began with First Blood (1982), based on the book by David Morell who created the now legendary and troubled Vietnam vet John Rambo. While the Rambo franchise is eternally connected to Sylvester Stallone, there were a range of actors considered for the role including, according to the New York Times, Paul Newman, Al Pacino, Robert DeNiro, Steve McQueen, Nick Nolte, John Travolta, Powers Boothe, and Michael Douglas.

Carolco had purchased the property from Warner Bros. and quickly landed on Stallone for the lead role. “This was kind of a Rocky movie,” said Vanja, “this was an underdog who was mistreated and manhandled and was fighting for the right to survive.” Despite the range of talent and personalities considered for the title role, it was Stallone who put the final touch on if the character was going to be a psychopath or some kind of underdog antihero. “What I did with Rambo was try to keep one foot in the establishment and one food in the outlaw or frontier image,” Stallone told the Los Angeles Times in 1985. While there weren’t initial plans for a sequel, $125 million sales on a $15 million budget proved that the story struck a chord with the public and Carolco was quick to put a sequel into production.

Kassar and Vajna had a definitive property along with a definitive star to build their image around. Rambo: First Blood Part II (1985) coincided with the ten-year anniversary of the U.S. departure from Vietnam along with a newfound patriotism regularly reaching jingoistic heights during the Reagan-era. Rambo became the defining property of Carolco and second films incredible profit — $300 million against a $25 million budget — paved the way not only for future Carolco films but became a proven industry practice that created opportunities at other independent studios like rival Orion Pictures to produce big films like Platoon and Robocop.

During the studios fast rise in the late 1980s, Carolco also picked up distribution for unique horror films from auteur John Carpenter with Prince of Darkness (1987) and They Live (1988). Carolco also landed another big action star in Arnold Schwarzenegger for the late Cold War action-buddy-cop film Red Heat (1988) directed by Walter Hill. Red Heat topped the box office while Stallone’s Lock Up (1989) lost money during exhibition. Other attempts at expansion, such as purchasing the competing Orion, fell through.

Vajna left the company in 1989 and a year later Kassar was known as “the billion-dollar man” for his ability to continue landing top talent with seemingly unrestrained salaries and bonuses. “I’m creating a stable of directors,” Kassar told the Los Angeles Times in 1990, “the directors attract the good material, and the good material attracts the good talent.” Having name-brand writers, actors, and directors attached to a project makes it easier for global distributors to put money upfront. The idea of a stable of reliable directors was also standard practice in Hollywood’s Golden Age. Certain filmmakers’ image was irrevocably linked to their contract home during a given period – Frank Capra and Columbia, John Ford at Fox, or Billy Wilder at Paramount.

Carolco was riding high in 1990, with massive hits like Total Recall (approx. $200 million profit) while films like the very good Narrow Margin and Jacob’s Ladder had minimal success. To offset the debt taken on by less successful films as well as fund the exorbitant production costs for projects in the pipeline, Carolco sold many shares to Japanese electronics company Pioneer. After all, something had to pay for gifts like the $14 million private jet Carolco gave to Arnold. As the New York Times wrote in 1991, Carolco “helped to drive up costs for the entire industry, and that has not endeared them to their peers.” The studio’s “reputation on Wall Street is not much better,” continued the Times, noting that Carolco stocks were hurting due to the company’s dedication to the ‘big-budget gamble.” However, it was the dedication that made the Carolco name in the first place. The cost of maintaining that image became more difficult over time. “We’ve moved well beyond any question of our viability,” said Peter Hoffmann, as he maintained their image as untouchables in Tinseltown.

When Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) made about $500 million on a $100 million dollar budget, it appeared like Hoffman’s words still held. The film was not only a massive win at theaters, but the apocalyptic man vs. machine epic is also often noted as the greatest action film of all time and reigns inarguably as one of the best sequels in history. Soon, Carolco ran up the bills again paying the unheard-of $3 million price tag for Joe Eszterhas’ Basic Instinct (1992) script.

The investment paid off, yet again, with a $350 million dollar box office run against a $50 million budget, while also pushing boundaries of the sexual thriller with fearless direction from Paul Verhoeven. Another sci-fi action thriller Universal Soldier (1992) starring Jean-Claude Van Damme and Dolph Lundgren was profitable while the critical darling and Oscar-winning Chaplin starring Robert Downey Jr. (1992) lost about $20 million.

The king of action production powered forward with Cliffhanger (1993), starring Stallone and directed by Renny Harlin, a stellar man vs. nature and man vs. his past thriller. However, budget overruns led to increasing concerns on top of the mountain of debt that was coming due for Carolco. Once again, the banks extend the loans and Carolco went running for more funding for the next hit that would, hopefully, save the company as they began missing debt payments. Global theatrical runs kept the company from bankruptcy. Roland Emmerich’s sci-fi adventure Stargate (1994) gave hope while maintaining the action-driven image that had become Carolco’s stamp on Hollywood.

The end was nearly inevitable with Paul Verhoeven’s Showgirls (1995). The hypersexual drama, controversially starring Elizabeth Berkley less than a year from starring in the teen sitcom Saved by the Bell, landed an NC-17 rating that hampered distribution. Now considered a cult classic in some circles, the film did not win over critics with its exploitive nature.

Showgirls would not make any money until a home video release, forcing Carolco to bet on the next big thing, a swashbuckling high seas adventure Cutthroat Island (1995). The trades reported that Carolco sold distribution rights for Showgirls to fund Cutthroat Island as one last desperate chance to climb out of crippling debt.

“They want to harvest their library (to remain solvent),” creditor Jeremy Bloomer told The Hollywood Reporter in August 1995, “it’s just an insufficient revenue stream for the debt load [$14 million] that they presently have.”

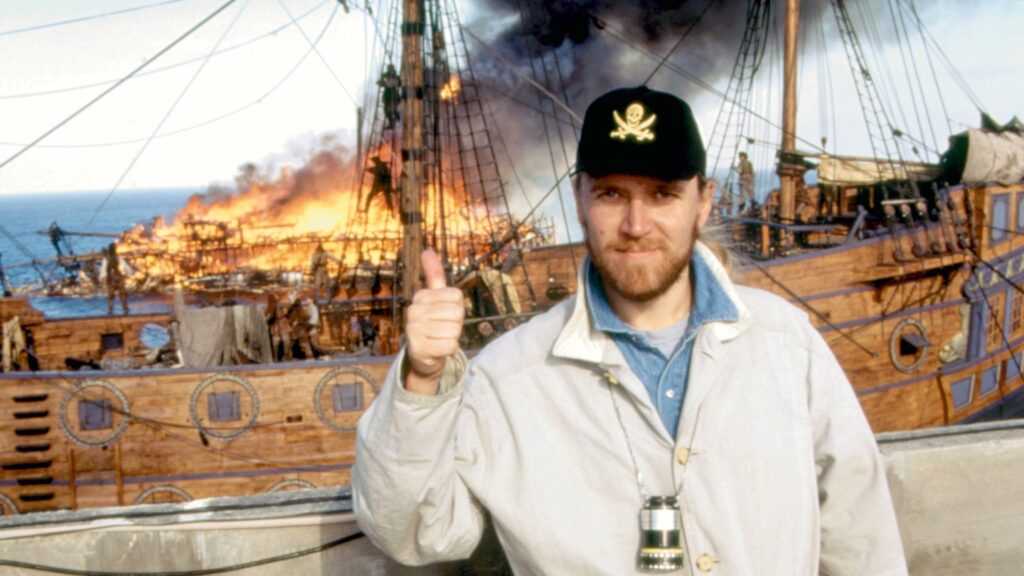

Months before filming began on Cutthroat Island, its star, Michael Douglas, jumped ship. Keanu Reeves, Michael Keaton, and Kurt Russell were all considered as replacements. Carolco landed Matthew Modine to star alongside the director Renny Harlin’s wife Geena Davis. The production itself had one calamity after another. A cinematographer got hurt, people quit, sets caught fire.

Carolco filed for bankruptcy in November 1995, a month before the film’s release. All “partners for the most part have already written off the investment as a total loss,” wrote The Hollywood Reporter. It did not help that the press reported that Carolco advanced Harlin $500,000 allegedly to pay for his wedding to Davis. Carolco executives believed salary reports hurt box office in the past, but details were hard to ignore as they were a part of the “Carolco premium.”

It was the end for Carolco. Ultimately, Cutthroat Island made $16 million on a budget of well over $100 million. In the end, Carolco was stripped for parts and its assets were sold at auction in 1996. Vajna had been gone from the company for six years, Kassar stayed as long as he was contractually obligated. The Rambo film rights were up for grabs as well. The remains of Carolco ended up in litigation over debt for some time including tax evasion from Peter Hoffman. “I am not a cheat,” Hoffman told a grand jury in 1997 claiming portions of his income were loans.

In recent years, Hoffman wound up pleading guilty to filing false tax returns to the IRS. Of course, the many stars and directors associated with Carolco continued. Stallone and Schwarzenegger were some of the biggest stars of the late ’90s. Directors like Oliver Stone and Roland Emmerich made even bigger films after Carolco while James Cameron directed the biggest film in history (Titanic, 1997).

The Carolco premium may not have always paid off at the box office but when it did, it won big. Though it ultimately fell apart, Carolco will always have a storied place in entertainment history. Carolco showed kids of the 80s what it meant for something big to be on the Big Screen. Carolco’s ripple effects are nearly immeasurable. Action films like Aliens (1986) Predator (1987), Robocop (1987), and True Lies (1994) may not have happened without Carolco paving the way for unapologetically big movies that defined the 80s and early 90s. The blockbuster mantle continued with people like Jerry Bruckheimer and Michael Bay.

Carolco may be long gone, but the modern action genre remains irrefutably in its debt.

Read the full article here