Yoshitoshi Shinomiya didn’t arrive at feature filmmaking via the usual routes of the Japanese anime industry. A traditional Japanese-style painter by training, and a longtime visual collaborator to filmmakers including Makoto Shinkai and Sunao Katabuchi, Shinomiya has built a reputation as a meticulous image-maker — an artist attentive to light, texture, and the emotional weather, unique to the expressive range of anime, that hovers somewhere between memory and landscape. He created the unforgettable flashback sequences in Shinkai’s acclaimed breakthrough, Your Name., crafted special scene work for Katabuchi’s award-winning In This Corner of the World, and moved fluidly between gallery installations, TV commercials and music videos before finally turning, after years of development, to an original anime feature of his own. That film, A New Dawn, made its world premiere this week in the main competition of the Berlin International Film Festival.

Set in a rural town where a long-standing fireworks factory faces eviction to make way for redevelopment, the story follows Keitaro, the son of a vanished fireworks artisan, who has secluded himself in the shuttered workshop in pursuit of a mythical firework known as “Shuhari.” As a typhoon approaches and the deadline for his home’s demolition looms, Keitaro reunites with his childhood friend and estranged brother for one final, desperate attempt to ignite something enduring above a landscape transformed by land reclamation, solar farms and the slow erosion of traditional Japanese communal life.

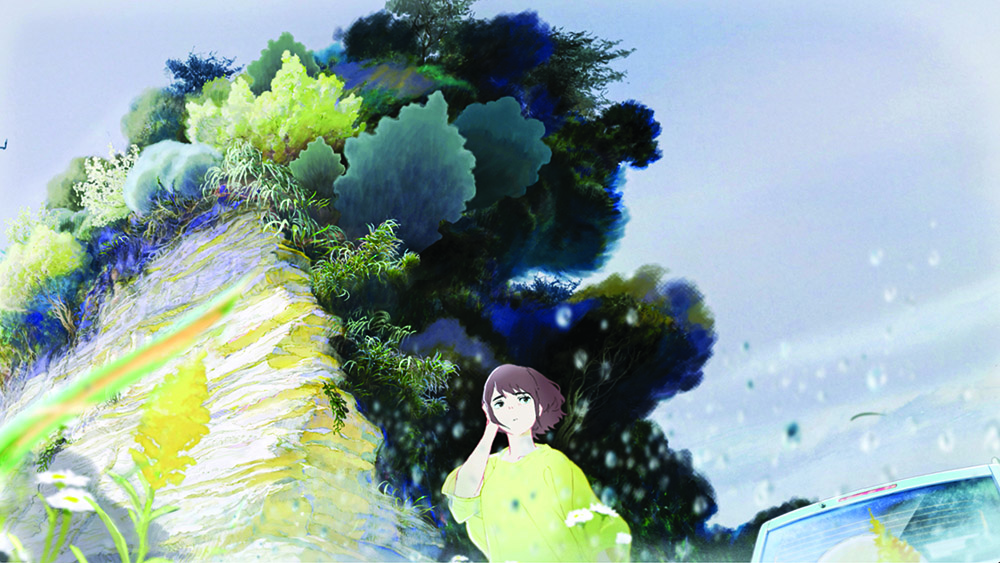

What begins as a coming-of-age drama gradually opens into something more searching and ambiguous: a meditation on inheritance and departure, on the uneasy collision of environmental urgency and cultural tradition, and on the question of whether deep cultural heritage can be preserved without being embalmed. Shinomiya’s sensibility — steeped in painterly craft and handmade ideosycracy, resistant to digital smoothness — lends the film a tactile quality that mirrors its thematic preoccupation with craftsmanship, ritual and reverence for the old ways.

Ahead of the Berlinale, The Hollywood Reporter connected with Shinomiya in Japan to discuss the images that sparked the project, the philosophical roots of the film’s central “Shuhari” metaphor, his complicated feelings about legacy and leaving home and what he learned from years spent working alongside master animator Makoto Shinkai.

Tell me about the inspiration and creative evolution of A New Dawn.

I had been preparing to direct a film project of my own for some time, but the direct trigger came around 2016. I have a building that I use as my atelier. In front of it there used to be an open field. Then one day, the entire field was suddenly covered with solar panels. For me, it was suddenly a landscape I couldn’t quite process — I didn’t know whether to see it as something negative or positive.

At one moment, my daughter saw it through the gaps in the trees in front of our building and said, “Oh, wow — is that the sea?” But when my daughter asked, “Is that the sea?” I suddenly realized: this is how children see things. They’re imagining a landscape in ways adults never would have imagined. That felt very meaningful to me.

When I was young, my hometown was a seaside town. The setting of this film is also based on that town. There was a period when the sea there was reclaimed as part of a land reclamation project. Suddenly, the seaside where I had always swum disappeared. I became fascinated by that kind of misalignment between lived reality, narrative and memory — between what’s actually there and how it is remembered or imagined. I decided I wanted to express that.

How did some of the other themes make their way into the story — family legacy, the bonds of childhood friendship, the impact of urban sprawl and rural depopulation?

The way communities exist and evolve is a central concern. On a smaller scale, that means family; on a larger scale, it means a village or society. Issues like new forms of energy, natural disasters, global warming — these forces are now eroding traditions and cultures that once continued almost effortlessly in Japan. In both good and bad ways, we’ve reached a time when change is unavoidable. Within that context, one major theme is how traditions, families and communities can endure — or whether they actually can. On a personal level, I grew up in the countryside and my family also ran a long-running family business — high-seas fishing. But I didn’t inherit it, as my predecessors had; I chose the city and this profession instead. So perhaps there’s something like a settling accounts in this work — or not exactly that, but trying to affirm my own choice. How can I justify, in my own way, the path I’ve chosen? That’s something I’ve had to process internally. It was certainly a significant element.

The “Shuhari” firework, which holds a somewhat mythic place at the center of the film’s story, is quite mysterious. I imagine you wanted to leave interpretation to the audience, but what does it mean to you?

The Japanese word and concept of “Shuhari” is very old. I believe it was first articulated by [the 16th century tea master] Sen no Rikyū. It consists of three characters: shu (to follow or protect), ha (to break) and ri (to separate). It describes the three stages of mastery or learning.

First, you follow the rules. Next, you break them. Finally, you transcend them and leave them behind. It’s traditionally used in fields like martial arts, theater, music and the arts. Ultimately, it describes human growth.

In the final stage, you leave the place you came from — whether that’s your parents, your community or your discipline. You grow, you depart — and perhaps someday you return. In the film, I liken the protagonists’ growth to this idea of Shuhari. It may not be a word that all Japanese people know deeply, but that concept of growth is embedded within it, and it informs many aspects of our culture.

How did you translate that deep concept into the shape of a single firework, that would serve as the movie’s central motif?

The motif of fireworks is also connected to my hometown. In the early 2000s, the annual local fireworks festival, which had existed for countless years, suddenly disappeared. The community felt they could no longer carry it on. Around the same time, the seaside was lost to reclamation as well.

I realized that even traditions that seem permanent can vanish surprisingly easily. Fireworks were once connected to our annual festivals and Shinto rituals — something almost sacred — but if people don’t actively protect them, they can disappear quickly.

If you just say “fireworks,” it may be hard to grasp the meaning. In written Japanese, the word includes the Chinese character for “flower.” A flower blooms for an instant and then disappears. That fleetingness has a strong affinity with artistic expression.

Since this is my first feature film, I wanted to lean into what I can express strongly. I’m good at drawing effects by hand — things that aren’t human. Nowadays, many such things are replaced with CG, but this is a film that foregrounds human craftsmanship. I wanted to show something created by hand. And in cinema, if you think of it as pure entertainment, it’s fundamentally sound and light. Fireworks embody those two simple elements more directly and more purely than anything else. There are other reasons too, but those are some of the main ideas.

But in the film, “Shuhari” is not just a concept but the name of a specific firework. Why did you give that metaphor such a singular form?

Well, it is very metaphoric. As we discussed, shuhari ultimately means mastering something and then leaving it behind — that’s essential.

The father, a fireworks maker, imagined launching fireworks over the sea so they would bloom both above and be reflected from below, like in a mirror. But the next generation cannot recreate that effect because the environment has changed. The sea is gone, filled in with land. The same conditions no longer exist.

So how do you inherit a technique when you cannot reproduce the exact circumstances from which it emerged? This is a plight many in various cultural fields in Japan might understand. You must reinterpret it in your own way. In the film, solar panels happen to serve as a substitute reflective surface.

This embodies the process of protecting, breaking and leaving — how something is passed on even though it is not identical. Techniques evolve gradually; they are never exactly the same. In establishing oneself, there is incremental progress and transformation.

In the modern era, we cannot recreate the same landscapes or environments as before. Environmental issues make that inevitable. So how does our generation — and the next — overcome that, while also honoring tradition?

As an artist, I also think about today’s world, with growing tensions between anti-globalism, communitarianism and libertarianism. How can art create expression within that? Can it find harmony?

This film is my attempt to offer one answer through artistic means.

And are the tanuki (raccoon dogs) that appear briefly a deliberate reference to Pom Poko? I adore that film, and I was struck by how A New Dawn shares some themes with it.

In a way, yes. I adore it too, of course. It’s a bit like how if someone makes a mafia film, it inevitably references The Godfather. In anime, when you draw tanuki, Pom Poko is such a strong association. When you ask any anime artist to draw a tanuki, their interpretation will inevitably refer to Pom Poko. That just shows what a masterpiece that film is. Pom Poko also addresses environmental issues, so there’s a natural affinity. I’ve watched it so many times. Any direct influence probably came out unconsciously.

Given your work with Makoto Shinkai, viewers will naturally be curious about his influence on you too. How did that experience shape you as an artist or filmmaker?

Well, I’m fundamentally a painter, whereas Shinkai is very much a director. For a long time, I believed I could rely purely on the strength of images.

But when I look at Shinkai’s work, what stands out is his sense of balance. He has an exceptional ability to elevate everything into entertainment. At first, his visual quality is what draws you in. But when you look closely, it’s not just the visuals — it’s the precision of the cutting, the way images connect. In fact, that precision in his rhythm may be even stronger than the visuals themselves.

His sense of balance as a filmmaker is something I learned a great deal from.

The English title A New Dawn sounds hopeful — like a fresh start. But the film’s tone and ending feel more ambiguous, perhaps bittersweet. For you, how does the ending land?

It retains something like a “true ending” nuance. Fundamentally, I think it’s positive. But I’m very drawn to the endings of American New Cinema. When young people leave their community, where do they go? Might they someday return? That open horizon feeling. I’ve always loved endings that continue beyond the film — where, after it’s over, you still think about the characters. You wonder what they’re doing now. I wanted an ending where you can carry your emotions with these young people after the film ends. That’s why it takes that form. In that sense, leaving things to the audience’s imagination felt like the best possible way to go out.

Read the full article here