I’m not going to pretend that I remember Rob Reiner‘s work as “Delivery Boy” on Batman or as “Mitch” from a couple of episodes of The Beverly Hillbillies. For my purposes, Reiner’s television career began with Norman Lear’s All in the Family and Mike “Meathead” Stivic, which is a hell of a way to get your start.

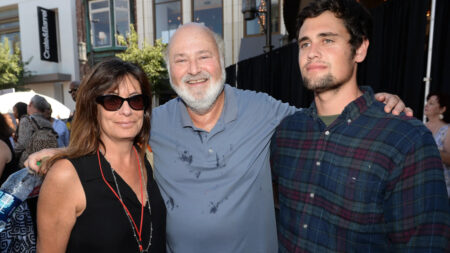

Being Carl Reiner’s son is a hell of a way to get your start, too. Reiner, who died this weekend along with his wife Michele, represents a best-case scenario of the phenomenon we’ve stupidly taken to calling “nepo babies,” as if going into the family business is an inherently problematic thing. Going into the family business is not an inherently problematic thing. Being elevated within that business beyond what you’ve earned is bad. But as much as Reiner arrived in the business with the most potent family connections imaginable, he also worked his way up, starting as, well, “Delivery Boy” on Batman and achieving his greatest initial fame as designated punching bag for a character with a permanent place on TV’s Mt. Rushmore.

The genius and lasting impact of All in the Family hinge on its uniquely inverted pyramid of empathy.

On any empirical level, Archie Bunker is the show’s villain. He’s a dinosaur. He’s a relic. (He’s also, as the show begins, younger than I am now. I need to work my way through that in a different forum.) He’s racist, sexist, homophobic, antisemitic, xenophobic, a blind patriot for a version of America that, as All in the Family began, had gone sour and would go fully rancid during the show’s run, with Watergate, the dying gasps of the Vietnam War and more.

But, at the same time, Archie Bunker is the show’s hero. He dominates the storylines, gets the biggest laughs from the audience and, as has been well-documented over the years, so convincingly and enthusiastically trumpeted his ideology that it was possible for people who would never have tolerated Norman Lear’s politics in real life to believe All in the Family was actually on Archie’s — and their — side.

Part of why that was possible was how clever and unflinching Lear and company’s writing for Archie tended to be. Part of why that was possible was Carroll O’Connor’s impeccable bluster. But perhaps most of why that was possible was Meathead.

Mike is, on an empirical level, the show’s hero. He’s consistently right, a product of his education — the show sees him go through college and grad school, and into teaching — and a product of being young at a moment when the counterculture had simply become the culture. Mike is the present and possibly the future. So any time Archie falls back on a stereotype or slur, every time he says something unforgivable, it’s Mike who has to roll his eyes, has to do a double-take, has to deliver a lecture, making it clear that Archie can’t say/do/think whatever he wants to.

For this reason, Mike is the show’s villain. He’s the pedant. He is, as Archie immediately dubs him in the flashback episode showing their first meeting, the “meathead.” Archie Bunker’s home is his castle and Mike is the invader, the interloper, the kid who infiltrated a grown man’s domicile, slept with his daughter, sat in his chair and had the temerity to tell him what names he shouldn’t call the Chinese or Jews or Blacks or women. The show knows Mike is right and it knows Archie is never going to fully change, and that’s a delicate balance that’s still astounding to watch even in 2025 — and even more astounding for the percentage of the American population that still thinks Archie is right and Mike is a soy boy.

Though any mental image of All in the Family from a distance of decades puts O’Connor at the center, Reiner didn’t lack for acclaim. He won two Emmys for supporting actor. And deserved them. It isn’t easy what Reiner has to do opposite the far more experienced O’Connor, to be constantly run over by the bulldozer that is Archie Bunker and yet never get entirely flattened. Television is a medium often dominated by a certain kind of obstinate, bellowing patriarch, and it could be argued that nobody, not Jackie Gleason or Desi Arnaz, bellowed as vituperatively and yet lovably as Carroll O’Connor. But Reiner also bellowed exceptionally, and complementarily.

If a TV show in 2025 dedicated as much time to characters yelling at each other or expressing non-stop exasperation with each other as All in the Family, critics would call it shrill and strident. I know I would! But All in the Family still stands up, and the right/wrong and hero/villain discordance between Archie and Meathead is central to its resilience. There’s an art to being as wrong and as pugnacious as Archie, to being as righteous and shrill as Mike, and to maintaining that equilibrium in a way that felt and feels honest and, in their ongoing debate, thrilling.

After All in the Family ended, rather that sticking to the acting world and trying to mature in the public eye as an actor, going from Young Turk to éminence grise in front of the camera, Reiner let that maturation happen behind the camera. Much has been, and deserves to be, written about Reiner as a director, about the basically unprecedented seven-film streak from This Is Spinal Tap to A Few Good Men, in which Reiner went from one genre to the next, helming one exemplar after another, one perfectly rewatchable hit after the next.

Reiner was a great director, but he was every bit as much an advocate for righteous causes, just as his father was before him and just as Norman Lear was for his 100+ year life.

He fought to ban smoking in public spaces in California, led a variety of environmental and preservation causes and campaigned aggressively for political candidates, generally on the left. Most significantly, as co-founder of the American Foundation for Equal Rights, he led the fight against the same-sex marriage ban installed by California’s Prop 8.

Opponents often treated him as an extension of Mike Stivic, suggesting he was an interloper in the civic space, a liberal who liked to spoil other people’s fun. He was mocked on South Park and, for his political sins, he earned the badge of honor that is a repugnant posthumous social media slam from the less affable version of Archie Bunker whose comfortable chair is currently in the White House.

He was harder and harder to marginalize, though, because he became an avuncular figure as himself rather than as a character. Unlikely Meathead, a whelp who spoke from a position of occasionally whiny, frequently wet-behind-the-ears insulation from life’s realities, Reiner had gray in his beard and a lengthy track record of using his podium for good. You could see hints of the Meathead-esque Pollyanna in the unrelenting optimism of something like The American President, but his evolution was happening on many levels.

Reiner became an indispensable talking head for news networks and in documentaries, offering sage commentary on his own work, on his Hollywood journey and the friends he made along the way, on the issues he championed. One of his best projects in years, on both sides of the camera, was the HBO documentary Albert Brooks: Defending My Life, in which he and high-school classmate Brooks shared a lengthy, career-spanning conversation, one that I’d imagine plays with heartbreaking poignance today.

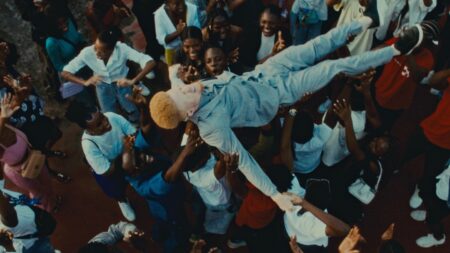

We never really saw Meathead mature into a father or grandfather or mentor, but every piece of Reiner’s professional and personal history came into play when he returned to acting, from his memorable run as Jess’ dad on New Girl to politically infused roles on The Good Fight and When We Rise and Ryan Murphy’s progressive industry fantasy, Hollywood. His last TV role will end up being an arc on The Bear as business consultant Albert Schnur, whose scenes encouraging Edwin Lee Gibson’s Ebra were among the highlights of the series’ fourth season.

There was always the tendency to call Reiner “Meathead,” just as some of us still call Ron Howard “Opie,” but the truth is that the real-life Reiner grew up in a way we only could have hoped Meathead might have done. I would always write “Meathead!” in my notes when Reiner popped up unexpectedly, but that was another of those All in the Family-esque inversions, a thing that started as an insult but became a term of endearment for an actor, director and champion of causes like no other.

Read the full article here