By all rights Among Neighbors should have been a run-of-the-mill documentary event.

Yoav Potash’s film — which explores a dark chapter of WWII — would normally be part of a reckoning that has been happening across Eastern Europe in recent years. The movie uses both animation and talking heads to examine the well-documented murder of hundreds of liberated Jews by local Poles at the end of the Holocaust, focusing on a few particular stories.

But Poland remains under the sway of the hard right Law and Justice party and its allies. So when the broadcaster, TVP, aired the movie and made it available for streaming last month, it wasn’t long before those politicians swung into action, with a high-ranking official in the office of president Karol Nawrocki saying that “a television station that has ‘Polish’ in its name should not have it on its airwaves” while others vowed to strip TVP of its license.

The controversy highlights how even rigorous historical inquiry has become charged in a world of right-wing populism and also gives more than a few echoes of Donald Trump’s pursuit of non-right-wing media in the name of patriotism back in the U.S. The Polish equivalent of the FCC has even joined the fight to go after the broadcaster.

And the incident underscores how, for all the supposed saturation of Holocaust stories, even historically necessary retellings from the period can now become disputed events.

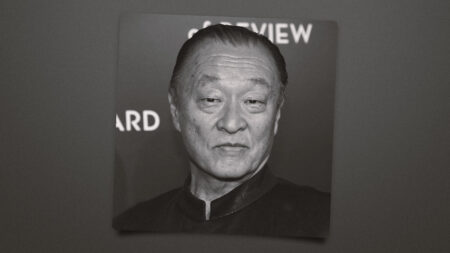

“It’s sadly predictable,” Potash tells The Hollywood Reporter. “My film is falling into an ongoing campaign that the far right in Poland has launched over the last decade to whitewash aspects of World War II. Any account where Poles are depicted as anything other than victims or heroes is anathema, a third rail and they flip out.”

While Poland’s government has for the past two years been center-left under prime minister and former European Council president Donald Tusk, the ultra-conservative Law and Justice party still has significant backing, winning more seats than any other in the 2023 parliamentary election; this summer the Law and Justice-blessed right-wing candidate and fierce Tusk antagonist Nawrocki also won the majority of the vote to become the country’s president and second-most powerful politician after Tusk.

Potash spent years developing and shooting his movie, keying on the town of Gniewoszów, and two survivors in particular who have an unlikely connection, Pelagia Radecka and Yaakov Goldstein, who are both seen on-screen in modern-day interviews with Potash. To put the viewer in the minds of the protagonists (and re-create scenes he didn’t have footage for), the SF-based filmmaker employed a dreamlike animation technique that holds its own with the likes of modern documentary classics such as Waltz with Bashir.

The movie garnered early grassroots love, including at a word-of-mouth screening hosted a year ago by Nancy Spielberg. It would go on to premiere at the Santa Barbara Film Festival several months later and got a theatrical release in New York and Los Angeles this fall with additional financial help from USC’s Shoah Foundation as well as the Jewish Story Council; it has also qualified for the Oscars. The movie will roll out in various cities for International Holocaust Remembrance Day on January 27.

It was also received well in parts of the country in which it was set, with a strong screening at the Warsaw Jewish Film Festival last year and a later pickup by TVP.

Yet Agnieszka Jedrzak, who serves as undersecretary to Nawrocki, posted on X after the premiere that the movie was “an anti-Polish historical manipulation,” also offering the comment about a broadcaster with Polish in its name. Some 4,000 people have liked the post, which has been viewed more than 300,000 times.

Meanwhile, Poland’s National Broadcasting Council, a group akin to the FCC, is launching an investigation with TVP’s license on the line. The agency’s chairwoman, Agnieszka Glapiak, a right-wing leader with strong ties to Law and Justice, has launched an “explanatory proceeding” involving the film and sent a letter to TVP asking it to provide materials defending the choice.

A TVP spokesperson did not immediately respond to a request for comment. The broadcaster previously told the Polish site Wirtual Media that it would continue to air the film. The movie’s goal “is to familiarize viewers with the complexity of Polish-Jewish relations, the positive and heroic episodes along with the tragic ones,” it said.

The 73-year-old public entity is the largest and longest-running Polish broadcaster but came under wide criticism during the run of Law and Justice, which had reshaped it, for becoming a far-right mouthpiece. It has been reshaped again in a more moderate direction under Tusk’s government.

While some of the response in Poland has focused on and twisted minute details — Jędrzak, the right-wing president’s deputy, also posted on X “Doesn’t the way the animation in the film depicts Poles during the occupation bother you? They have red, angry eyes, they denounce, eavesdrop, and track down Jews” — Potash says he simply was trying to tell an up-close story of a complicated place.

“A dark side, that six months after the Holocaust so many Jews were murdered when they came home from the camps, is front and center because that’s the story we were telling,” says Potash, who previously directed the well-regarded criminal-justice doc Crime After Crime. “What happened in our town was sadly not an isolated incident. But we’re also careful not to paint all Poles with the same brush; it doesn’t mean all Poles wanted Jews dead. There were heroes too. There were people sympathetic to Jews. And the film would not have been possible without the participation and cooperation of so many Polish people.”

Poland in the modern age has been grappling with a rise in antisemitism, with Grzegorz Braun, a far-right member of parliament and notorious antisemite, giving a speech last month outside the gates of Auschwitz saying that “Poland is for Poles; other nations have their own countries, including the Jews” and comparing Jews to Hannibal Lecter. He offered his comments on the anniversary of the day when 340 Jews were burned alive by their Polish neighbors in 1941 in an event known as the Jedwabne massacre. (Braun’s remarks were condemned by more moderate politicians.) A report last month also reported a 67% increase in antisemitism in Poland in 2024, while the country also has a law that imposes jail time for implicating Poland in the Holocaust.

TVP’s willingness to stand up and keep the movie on the platform, Potash says, was a laudable act in the face of these winds.

“Poland is a very divided society,” he says. “It can seem hard to square until you look at the United States and how we divided we are about Trump and so many different policies, and then it becomes a little easier to understand.”

The filmmaker didn’t specifically mention the administration’s targeting of news outlets and late-night personalities and media companies’ varying, often capitulative reactions to those efforts, but it was hard to miss the parallels. Reviewing the film, the independent San Francisco critic Dennis Harvey noted that “it’s a strong piece with particular relevancy at a time when our own leaders appear very interested in burying any unflattering aspects of U.S. history.”

While grateful for the support of Jewish organizations, Potash also says he remains a little flummoxed by mainstream U.S. neglect of his film — the major film festivals he said wouldn’t take it, the NY Times and LA Times didn’t review it and no streamer or distributor has yet bought it — despite the warm reception from those who have seen it and Potash’s strong standing in the doc world. (THR’s review of Crime After Crime called it “a powerful and emotional story of protracted injustice backgrounded by a potentially even more fascinating account of entrenched corruption in the Los Angeles D.A.’s office.”)

Among the reviews of his new film, however, there have been some puzzlers. While assessing the Holocaust picture, Film Threat, for instance, wrote that “Israel as a state is not exactly regarded sympathetically, given the flattening of Gaza. Despite Potash’s heartfelt accomplishments, now is simply not the time [to examine Jewish victims].”

Poland has been reckoning with its post-war history cinematically for some time. In 2015 Pawel Pawlikowski’s Ida won the best foreign-language Oscar for its understatedly powerful tale of how the Holocaust was — and wasn’t — discussed in the Communist-led nation in the 1960’s. The country has undergone a slower process of reconciliation with the past than neighboring Germany, owing in part to how it was occupied and victimized even as it was also producing Nazi collaborators and jarring acts of violence, making binaries difficult.

And information about the country’s wartime past has been hard to access for long stretches of the past 80 years given heavy government control of media, including the entirety of Cold War until 1989 and again this century with the eight-year reign of Law and Justice that ended in 2023.

“I understand why many in the country cling to the fantasy that Poland did no wrong and don’t want to accept anything that doesn’t make them feel patriotic,” Potash says when asked about the right-wing backlash to his film. “I’d like to think this is the growing pains of a dying argument. We’ll see if that turns out to be too optimistic.”

Read the full article here