Amid another anxiety-inducing year for the theatrical film business, one of 2025’s few unmistakably hopeful signs came in a most unexpected form: Japanese period drama Kokuho. A nearly three-hour epic set in the esoteric world of traditional kabuki theater, the film has defied all reasonable expectations to become both a critical darling and Japan’s most commercially successful live-action film of all time.

The film premiered to quiet acclaim in the Directors’ Fortnight section of Cannes in May, releasing in Japan shortly after and becoming a word-of-mouth sensation, eventually earning more than $112 million. After a brief awards-qualifying run in Los Angeles and New York this fall — a full U.S. theatrical release is expected in early 2026 — it is now considered a strong Oscar contender in the best international film category.

Directed by Lee Sang-il, Kokuho (which translates to “national treasure”) adapts an 800-page, two-volume novel by acclaimed author Shuichi Yoshida, who spent several years embedded backstage as a kabuki stagehand while researching the tradition. The story spans five decades in the lives of two intertwined performers — an orphaned onnagata prodigy (a male performer specializing in female roles) and the heir to a great theatrical lineage — whose friendship is twisted by obsession, rivalry and, eventually, transcendence. As THR’s review noted, Lee crafts a “transporting and operatic saga that blends backstage melodrama, succession drama and a making-of-an-artist narrative into a sweeping meditation on ambition, beauty and sacrifice.”

Born in Niigata in 1974 to a Korean-Japanese family, Lee climbed the rungs of Japan’s arduous indie scene in the late 1990s before breaking through with Hula Girls (2006), a warmly humanist crowd-pleaser that swept the Japan Academy Prizes and established him as a filmmaker capable of pairing populist storytelling with sharp social observation. He followed it with darker, more morally fraught work — including the acclaimed crime drama Villain (2010) and the ensemble tragedy Rage (2016) — often drawn from the fiction of Yoshida, his consistent creative collaborator. Lee recently gained a touch for the high gloss of prestige TV, directing three episodes of Apple TV+’s Pachinko.

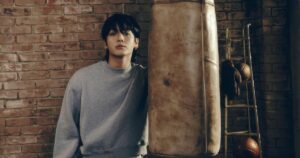

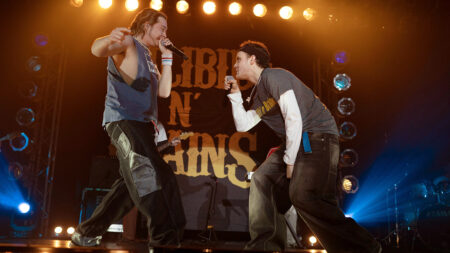

But Kokuho is arguably his most personal undertaking to date — a 15-year passion project brought to life through nearly two years of rigorous kabuki training for stars Ryō Yoshizawa and Ryusei Yokohama, under the supervision of master actor Nakamura Ganjirō IV. Their performances, one icy and incandescent, the other warm and wounded, are among the film’s defining marvels, anchored by Ken Watanabe’s gravitas as the patriarch whose authority shapes their ascent, and electrified by the uncanny presence of dancer-actor Min Tanaka, whose embodiment of an elder onnagata lends the film a haunting spiritual undercurrent. Shot in just three months but shaped by years of training and rehearsal, Kokuho’s immersive kabuki sequences — captured in mesmerizing closeups by cinematographer Sofian El Fani (Blue Is the Warmest Color) — have been credited not only with reviving Japan’s theatrical box office but also reigniting public fascination with the centuries-old art form, as major kabuki venues across the country have recently reported surges in attendance, even among younger demographics.

After a long lap through many of the world’s top festivals, Kokuho screens this week at Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea International Film Festival.

The Hollywood Reporter recently spoke with Lee over Zoom about his long fascination with onnagata performers, how he set out to “bathe” audiences in kabuki rather than explain it, the metaphysical ideas behind Kokuho’s most enigmatic images and what it’s been like to watch his three-hour drama become a genuine cultural watershed in Japan.

How did you first become interested in kabuki as the subject for a film?

I first became interested in a very famous onnagata named Utaemon Nakamura. He was widely considered the greatest onnagata of the postwar period. He became a national treasure by sheer skill, and there was no border between his personal life and his life as a performer. I’d seen videos of him and felt that he had a special energy. That’s kind of where my interest stemmed from.

After I made the film Villain, based on the novel by [Shūichi] Yoshida, I told him about this idea I was thinking about for a film based on a great kabuki actor. Later, he began writing the book that Kokuho is based on. In his novel, the character closest to Utaemon would be the onnagata Mangiku, played by Min Tanaka. I didn’t chat with Yoshida much while he was writing the novel, but I think my original interest helped plant the seed for him. And of course, once he was finished, we began working on adapting his wonderful novel.

Kabuki is a codified, traditional art form that can feel remote or austere to people who are unfamiliar with it. How did you approach the central challenge of making this world accessible to newcomers?

When thinking about making any film that features kabuki heavily, something important Mr. Yoshida’s writing already included is this conflict between preserving the performer’s bloodline and the limited opportunities for outsiders, like Kikuo’s character. The traditional kabuki world hinges upon this passing down from father to son, and there is a lot of dramatic potential in this.

The second theme that felt universally accessible is the kabuki artist’s pursuit of beauty. How do these kabuki actors relate to beauty, and how does it affect their life off the stage? Kokuho is a story about kabuki, but it’s also simply a story about an artist seeking the light, trying to go as high as he possibly can. There’s immense personal sacrifice that comes with that. The most interesting element for me is that these actors put everything into their pursuit, to the point where there is no boundary between their stage life and their personal life. I felt that following the trials and tribulations that come with that kind of total commitment offered the potential to create a timeless epic.

I was surprised by how much actual kabuki performance the film contains — and how artfully you integrate it with the drama, how immersive it is rather than didactic. What were your priorities when it came to how you would portray the kabuki stage cinematically?

There are over 200 kabuki plays, and if someone wants to really experience the art form, they should just go see some actual kabuki. I knew that if I tried to make the film an “introduction to kabuki” it would be lacking — it would be an incomplete representation of a full performance, and it could easily become boring for people who aren’t already familiar or fans. So, it was very important to connect the characters’ personal drama to the stories within the kabuki plays. That’s how I chose which plays to include — based on what would reflect their internal life the most. The challenges the characters face in their personal lives needed to be paralleled within the kabuki performances.

I wanted the audience to feel like they were almost bathing in this film. I strove for it to feel that way while I was shooting — so that the audience would directly feel emotion underneath the makeup, the costumes and these ancient sagas.

The original Yoshida novel also has that parallel very strongly. For example, while performing the play Sonezaki Shinjū, Kikuo portrays this moment where there is a suicide — and this comes just as he’s recognizing that he’s willing to die for his art too.

Off the timeless kabuki stage, the film is also a period drama spanning some 50 years. The period details are subtle and beautifully realized throughout. It can be hard to shoot period films in contemporary Japan, because the look of the cities has changed so dramatically. How did you approach this challenge?

Well, the visual mission of this production was kind of twofold. First, the kabuki had to feel extremely authentic. Second, we had to make sure that the five decades the film covers felt right at every time period. Rather than separating those things, we took one theoretical approach. Usually, when you show different time periods, films use TV screens or different cityscapes in VFX to show the passage of time. But for Kokuho, I wanted it to feel like the audience was watching one continuous giant opera. So instead of using obvious time markers, I talked with the production designer about how we could subtly show the period changes in the smaller backstage environments where these characters actually spend much of their time.

In terms of cinematography, I was inspired by Soderbergh’s Traffic, where he used three completely different color tones. I didn’t want to be that obvious, so we changed the color grading slightly for the three different time periods shown over the 50-year sweep of the story, creating three different looks. They’re not extremely obvious — they’re subtle enough that audiences might or might not even consciously notice — but they have a subconscious effect.

Of course, we changed the hair and costumes depending on the time period, too — and that involved hundreds of people for each period.

I understand that Ryo Yoshizawa was the only actor you even considered for Kikuo. What qualities did you see in him that convinced you he could carry such a demanding, complex role? Similarly, what made you feel that Ryusei Yokohama was right for Shunsuke?

First, for Ryo Yoshizawa, the reason I felt it had to be him is that he has tremendous outward beauty, and he also has this internal world that gives a feeling of immense openness — like a giant open space. At the same time, he has a very strong passion deep within. That might sound a little abstract, and those two things seem opposite, but together they create a unique charm, which I felt would work really well to portray Kikuo’s complexities. That’s something only Yoshizawa has.

For example, one of my favorite sequences: the rooftop scene after he’s fallen from fame, he’s been beaten up and does a drunken dance on the roof. He’s beautifully expressing a form of madness, but he also preserves a kind of hard logic at the same time. Those two sides conflict within him, and outwardly, he still looks like this beautiful ceramic doll. He’s just the perfect fit for the character.

Regarding Ryusei Yokohama, I felt he was very complementary to Kikuo, because he’s very human and very loving. In real life, he’s also a very hard-working, respectable person. He’s honest about his own desires and still very lovable.

These two characters share the same passion, but in very different forms. Shunsuke is like a red-hot flame, while Kikuo is more like a dry-ice kind of heat. In both cases, if you get too close, you can be burned. That’s the way I like to think about the two of them.

Were there moments when you deliberately decided to take dramatic liberties in your depiction of kabuki, or did you strive for total realism at all times?

Well, when I began working on the film, I did a lot of research. I wanted any liberty that I eventually took to be fully deliberate. So I read books and novels, watched lots of videos — to build a historical and technical foundation. Then I watched loads of kabuki performances. None of our cast are actual kabuki actors. They started from zero, so we had professionals train them, and I watched the training as well. I got to see how they were trained and how movements get built into the body. So I learned as they learned. We had a kabuki advisor on set who checked every movement for authenticity.

But within that authenticity, we made sure we could still feel Kikuo — that we see Kikuo the character performing kabuki, which means some of his personal emotion seeps in. Normally, that isn’t at all done in an actual kabuki performance.

For example, in the ending sequence of Sonezaki Shinjū, Shunsuke’s face is wet with tears. Normally, that sort of thing would be cleaned off in between acts or scenes. But as a movie, we felt it was better to see his emotion. We took an expressive liberty.

From what I’ve read, onnagata are traditionally described as channeling an otherworldly beauty that is neither male nor female. Was that something you talked to your actors about, and how did you strive for it? In particular, Min Tanaka, who plays the character closest to the real-life kabuki master you mentioned earlier, seemed to embody this quality in a very transfixing way. Every time he was on screen, I was wowed by what he was doing.

How I understand this aspect of onnagata being neither male nor female is that they are almost like a shadow, or an afterimage, or an illusion. It’s very subjective to understand what that is. I get it when I watch a truly great kabuki performance, but there are very few actors who can really do it, and it’s hard to express in words. It’s the sort of thing where, when you see it, you know it. It’s expressed through the body.

With Min Tanaka, in particular, he is someone who has devoted his whole life to expression through body and movement. That’s probably why you feel him so much when he’s on screen. I felt it too. He had never performed as an onnagata before, but he’s worked his whole life to merge body and soul through various dance disciplines he’s studied in the most devoted way one could imagine. This is my personal interpretation. Kabuki is about form, but if you only perfect the form, you become basically a highly accurate doll. When you put soul into that form, that’s when you get a true onnagata. I think Min Tanaka has that kind of silhouette — that presence — and that might be what you felt. That’s how I understand it anyway.

When you were describing that, it called to mind another enigmatic element of the film: your depiction of Kikuo’s vision — his artistic ideal, or what he’s striving for. That image that appears on screen in key moments — it looks like stars or gently falling snow. At the end of the film, when he’s reached his artistic triumph, he tries to articulate it when he’s asked directly by an interviewer, and he can’t really put it into words. At one point I wondered if it might be a bit “Rosebud”-ish, echoing the snow that falls when his father is assassinated at the film’s start. How do you understand it, and what were you going for in the way you depicted it on screen?

Well, it’s a little hard for me to express in words as well. [Laughs.] My understanding is that, in Kikuo’s life, his original encounter with something profoundly beautiful was his father’s assassination. Even though the death itself was brutal, the scene was very beautiful, and that was imprinted in his mind.

With all kinds of beauty, there can be an element of brutality. When Kikuo makes his contract with the devil to become the greatest kabuki performer in Japan, I think that symbolizes the idea that evil can charm — that’s what the devil is, in a way. Evil and beauty are kind of one, or evil can make beauty feel even grander.

He chases that feeling in his artistic life. The snow that turns into light is like the entry point into that beauty for him — and there’s something beyond it. It’s almost like that image is a curtain, and what lies beyond can’t really be expressed in words.

That’s a much more metaphysical, more interesting articulation of what I have read many critics articulate as the film’s central theme: the sacrifices required to become a truly great artist, the personal toll it takes. Kikuo loses so much in his ascent to the pinnacle of his art: people close to him, his moral integrity, any real community. He’s alone at the top. Is that true in your view? Is it possible to become a truly great artist and still be a good, balanced, normal person? Or is that deal with the devil always required to become truly great?

I feel like there are good people who became great artists, but there are probably few of them.

I would say sacrifice is not necessarily a given. It’s like a chicken-or-egg situation. For Kikuo, he prioritizes art no matter what, and things just fall through the cracks because of that. It’s not like he’s presented with a clear choice between art and other parts of his life. As he focuses so much on art, it’s like sand falling through his fingers — the other aspects of his life are slipping away.

It might not even be something he knows about himself — I’m not sure how aware he is of it — but I think that’s what helps express his maddening beauty.

For an artist, chasing greatness can seem like a selfish endeavor. I might be a little abstract here, but for Kikuo, I think he’s really chasing the experience of having the freest feeling. It’s like, with breath, the soul can be released. That’s the feeling he’s after.

Is that theme one you can relate to personally as an artist? This film was a massive undertaking — what did it take out of you?

I’m not that kind of person myself, but I was very interested in whether I could come into contact with it. As you can tell from how difficult it is for me to explain all of this, the film explores some depths — it felt like trying to swim to the bottom of a well. It was something I wanted to learn from or come into contact with. I was really chasing: What is that? The thing we’ve been talking about — the ultimate sacrifice, that beauty beyond. What is that thing, beyond logic, that makes a truly beautiful performance moving for an audience?

We should also talk about the phenomenon the film has become in Japan. It’s now the top-grossing domestic live-action film of all time. I’m curious about a few things: why you think the film has connected so deeply with Japanese audiences; what it was like for you personally to watch that phenomenon unfold; and what’s been most gratifying to you about the impact the film has had.

First off, I’d say that right now I feel like laundry in a washing machine. This has been a long, grueling journey — and the publicity part continues. To actually feel joy, I think once I’m hung out to dry on a sunny day, maybe I’ll start feeling it a bit more. [Laughs.]

In terms of why this connected so much, it’s difficult to express in words. Through the story of these kabuki actors, people got to witness a very human sacrifice across time — through training and tireless performance — and the hot burning of the soul when you watch them on stage. Then there’s the beauty of the image and the intensity of the sound in a movie theater. Altogether, as word of mouth about the film spread, it became a national, collective experience of a kind, which created a sense of something more than just watching a film.

In making this film, I had a simple motivation: to portray for modern audiences the totality of beauty, including those aspects touched by the devil — the brutality we talked about.

In our individual lives — with economic disparity increasing, which is becoming as urgent in Japan as elsewhere — I feel like the distance between people is also increasing. I wanted humans to witness the beauty of other humans. Maybe the film struck a chord because some of that intention made it through.

As a final question: like many viewers, I found that even though the film is nearly three hours long, it flew by — probably because of the immersive quality you’ve described. When it ended, I wanted more time with these characters. I was gratified to read the original novel was over 800 pages long, which means you must have had to cut out a lot. So: If you were asked or invited to direct a limited-series version of this story, to revisit it as a streaming project, would you say yes?

It would be incredibly hard to do that, given the way the actors prepared and trained specifically for this three-hour film. To have them start that engine back up again, or to bring in new actors and do the same thing, would be very difficult. So, I think probably not.

But like you’re saying, if audiences are interested in learning more about these characters and continuing this journey — well, since the movie came out, the original novel has sold four or five times more than it originally had. So that’s what I would recommend for audiences: read Shuichi Yoshida’s beautiful book. It will be translated eventually.

Read the full article here